Moonwalking with Einstein - Joshua Foer

📝 Notes

Focused on memory and how its processes work.

A journalist that does not have a particularly good memory went to cover a memory championship event. Intrigued and befriending some competitors, he starts practicing, and a year later wins the U.S. memory championship event himself. Inspiring dive into the subject of memorization.

One of the concepts which captured my attention was the 4.Archive/zettelkasten/memory palace that relates to the story of Simonides of Ceos who built a memory of a palace banquet hall and having survived the cave in of the building's roof was able to locate survivors and bodies by having memorized where everybody was sitting in a mental model of the palace.

This connection to the visual memory has a link with the Reticular Activating System and the benefits for example of sketchnoting.

Also the attempt to build these visual metaphors makes us have more mindfullness of the moment instead of letting the auto-pilot run and forget things easily.

Interesting that we use a term that clearly points to this concept, the term is memorabilia which is something that I keep to remember something of someone by. It is a visual cue of that event or person so clearly the human being knows that objects and visual metaphors are more resilient to the passing of time.

publish

Regular practice simply isn’t enough. To improve, we must watch ourselves fail, and learn from our mistakes.

The best way to get out of the autonomous stage and off the OK plateau is to actually practice failing.

(The phrase “in the first place” is a vestige from the art of memory.)

1 - The smartest man is hard to find

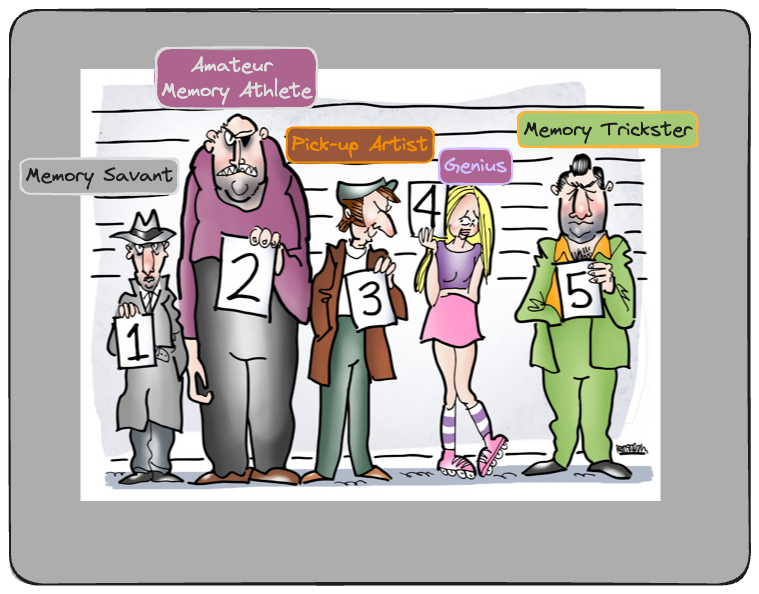

It is hard to find and even to measure who the smartest man is.

It is also easy to confuse people who can apply smart techniques for memorizing or reasoning with savants or geniuses.

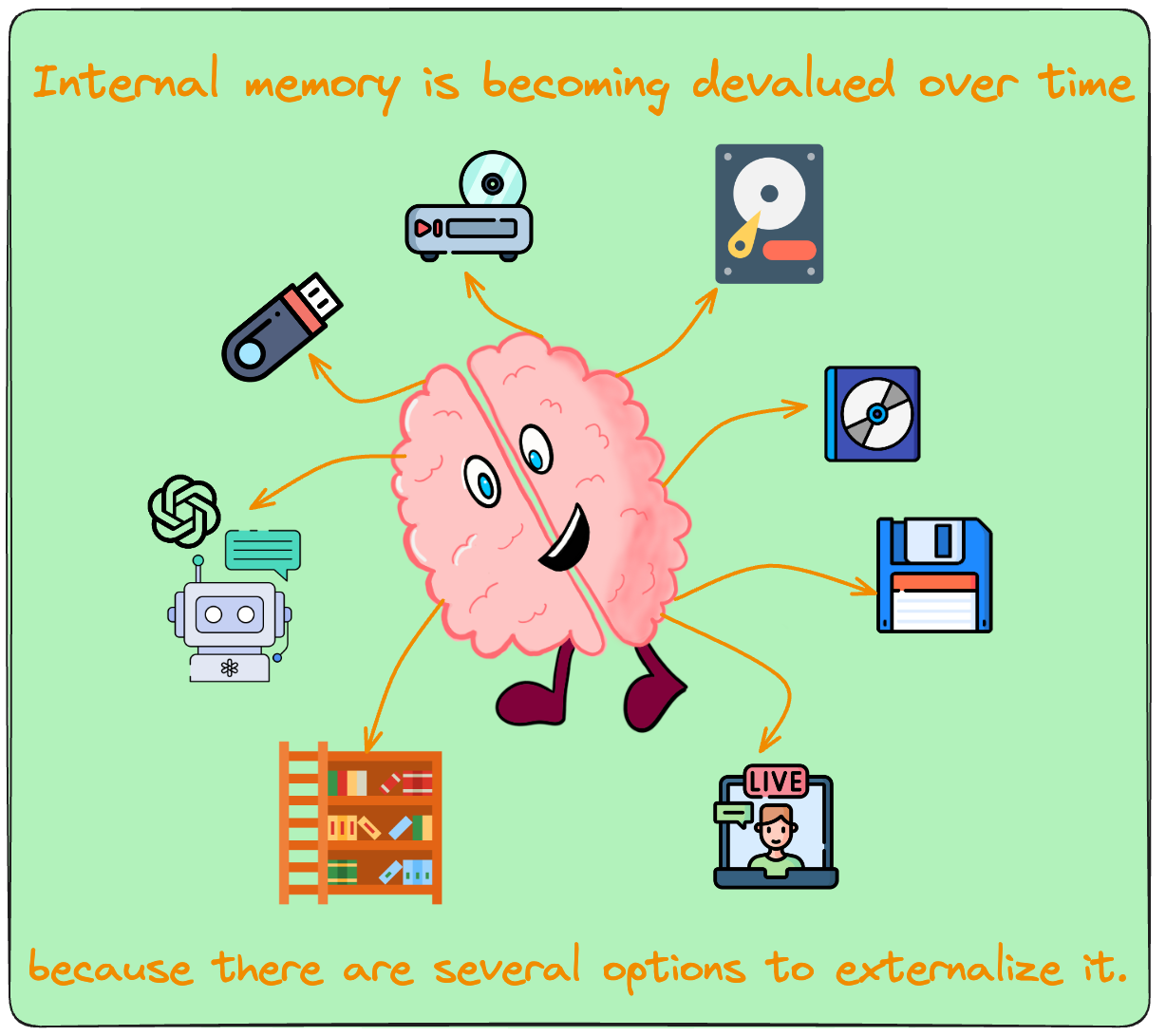

The externalization of memory not only changed how people think; it also led to a profound shift in the very notion of what it means to be intelligent. Internal memory became devalued.

Erudition evolved from possessing information internally to knowing how and where to find it in the labyrinthine world of external memory.

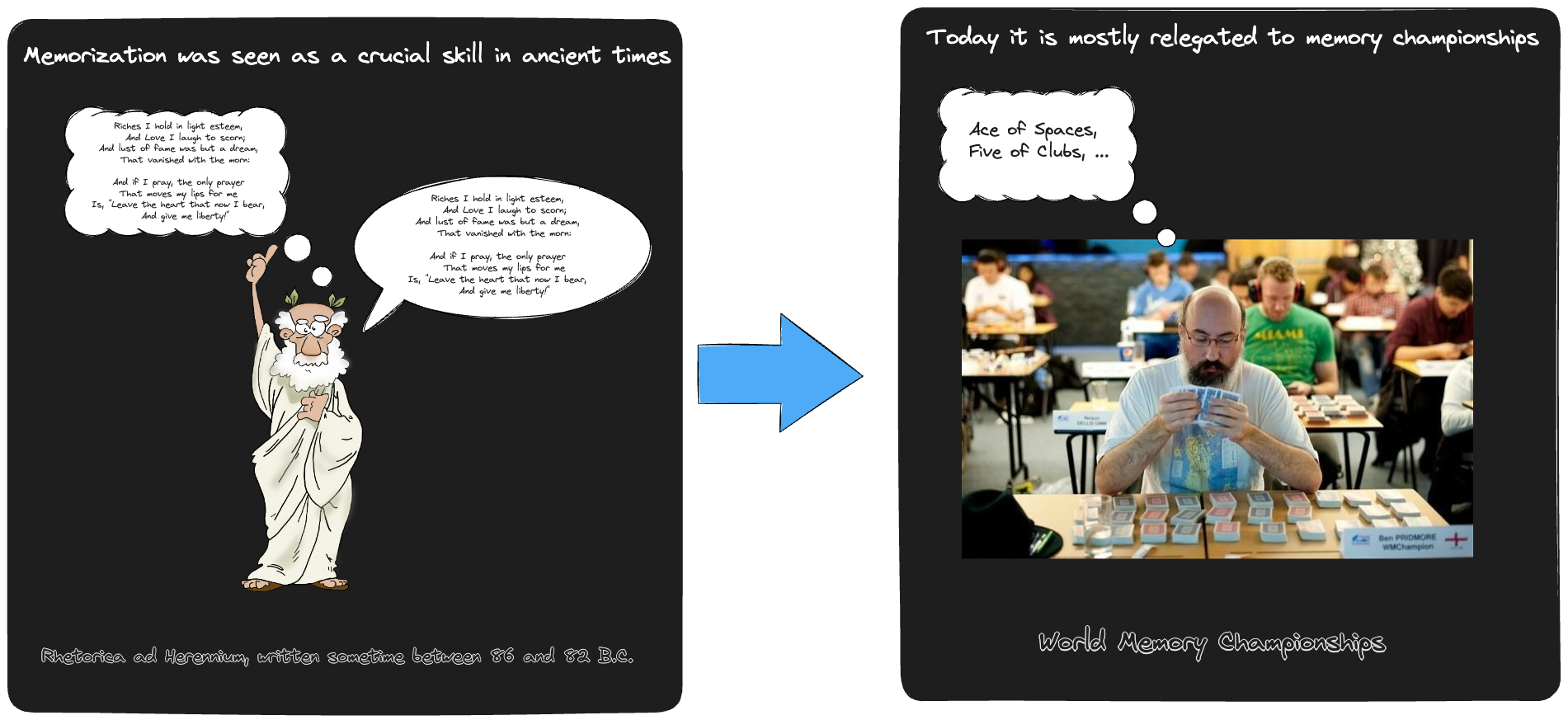

It’s a telling statement that pretty much the only place where you’ll find people still training their memories is at the World Memory Championship and the dozen national memory contests held around the globe. What was once a cornerstone of Western culture is now at best a curiosity.

But as our culture has transformed from one that was fundamentally based on internal memories to one that is fundamentally based on memories stored outside the brain, what are the implications for ourselves and for our society? What we’ve gained is indisputable. But what have we traded away? What does it mean that we’ve lost our memory?

2 - The man who remembered too much

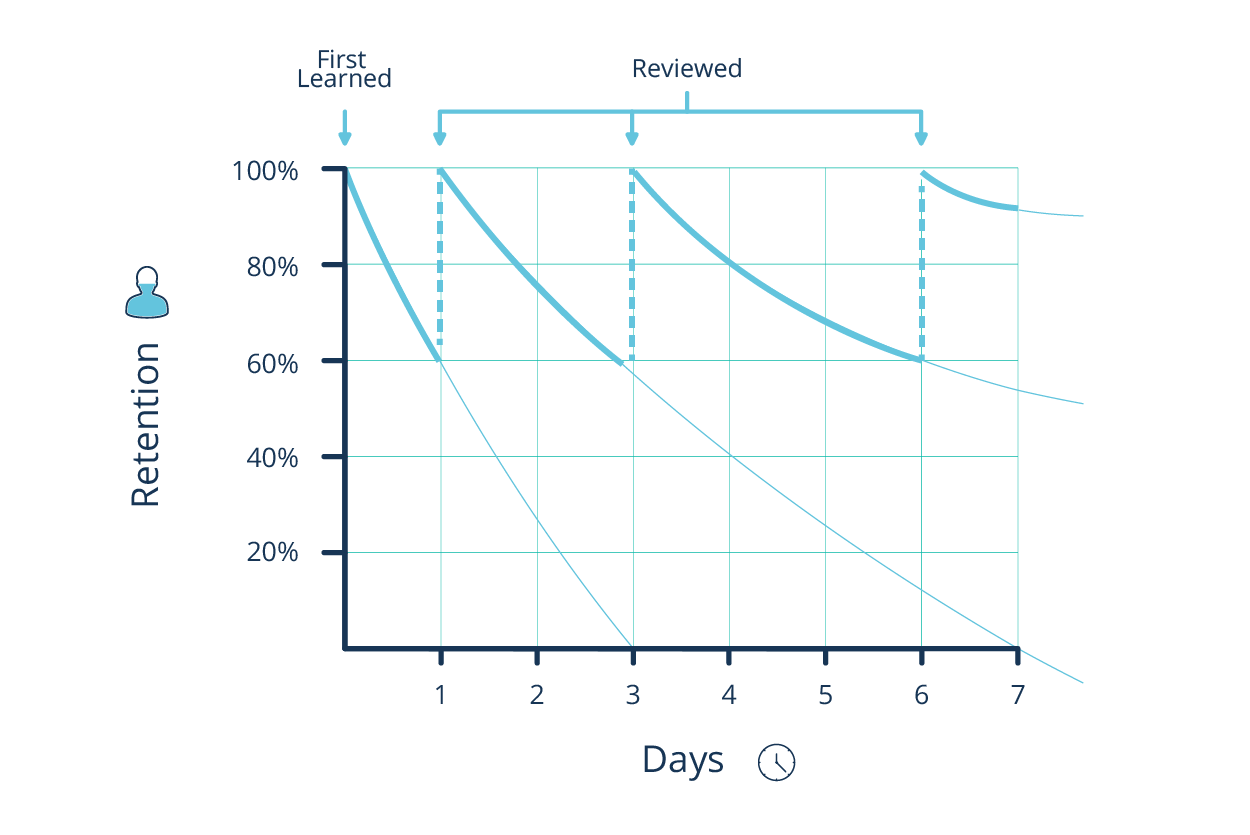

For normal humans, memories gradually decay with time along what’s known as the “curve of forgetting.” From the moment you grasp a new piece of information, your memory’s hold on it begins to slowly loosen, until finally it lets go altogether.

As neuroscientists have begun to unravel some of the mysteries of what exactly a memory is, it’s become clear that the fading, mutating, and eventual disappearance of memories over time is a real physical phenomenon that happens in the brain at the cellular level. And most now agree that Penfield’s experiments elicited hallucinations—something more like déjà vu or a dream than real memories.

Synesthesia

Every sound is associated with its own color, texture, and sometimes even taste, and evoked “a whole complex of feelings.” Some words were “smooth and white,” others “as orange and sharp as arrows.” The voice of Luria’s colleague, the famous psychologist Lev Vygotsky, was “crumbly yellow.” The cinematographer Sergei Eisenstein’s voice resembled a “flame with fibres protruding from it.”

Our Spatial Memory is very well developed evolutionary speaking.

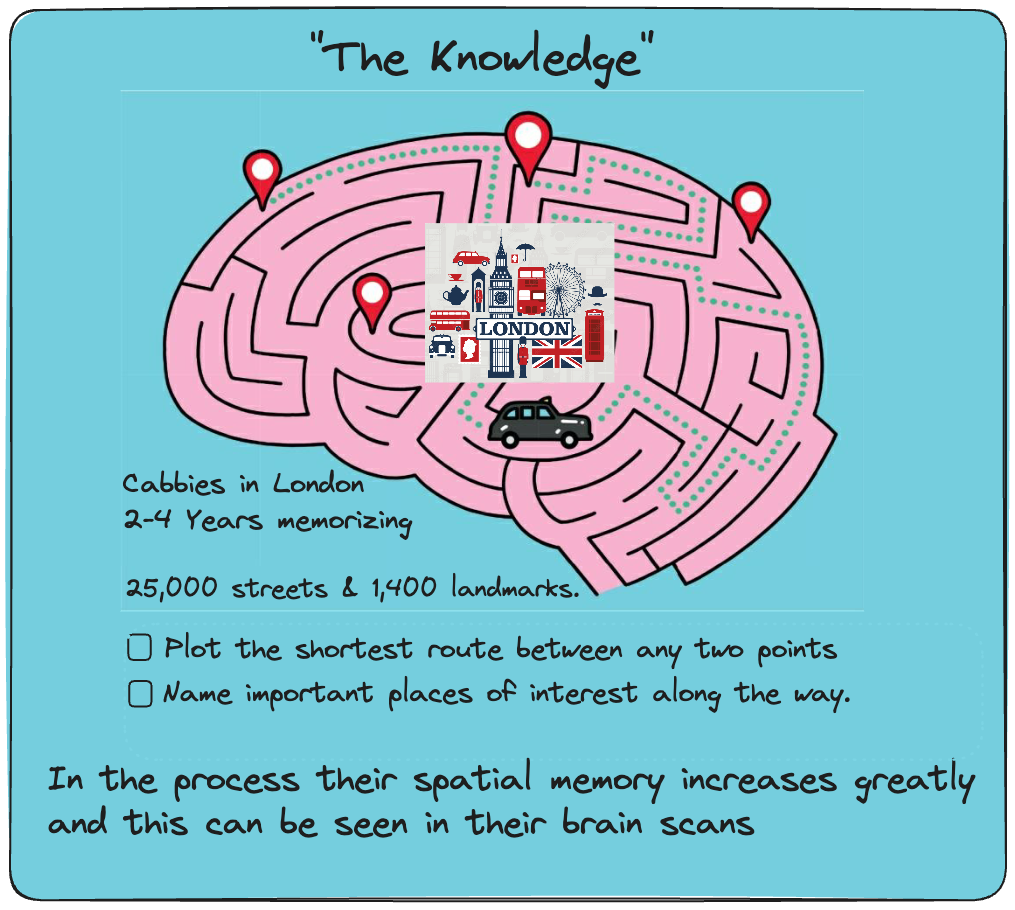

If you visit London, you’ll occasionally cross paths with young men (and less often women) on motor scooters, blithely darting in and out of traffic while studying maps affixed to their handlebars. These studious cyclists are training to become London cabdrivers. Before they can receive accreditation from London’s Public Carriage Office, cabbies-in-training must spend two to four years memorizing the locations and traffic patterns of all 25,000 streets in the vast and vastly confusing city, as well as the locations of 1,400 landmarks. Their training culminates in an infamously daunting exam called “the Knowledge,” in which they not only have to plot the shortest route between any two points in the metropolitan area, but also name important places of interest along the way. Only about three out of ten people who train for the Knowledge obtain certification.

In 2000, a neuroscientist at University College London named Eleanor Maguire wanted to find out what effect, if any, all that driving around the labyrinthine streets of London might have on the cabbies’ brains. When she brought sixteen taxi drivers into her lab and examined their brains in an MRI scanner, she found one surprising and important difference. The right posterior hippocampus, a part of the brain known to be involved in spatial navigation, was 7 percent larger than normal in the cabbies—a small but very significant difference. Maguire concluded that all of that way-finding around London had physically altered the gross structure of their brains. The more years a cabbie had been on the road, the more pronounced the effect.

3 - The expert expert

Working Memory 7 Items Limit

We cannot hold more than 7 items at a time in working memory is what the paper from George Miller from Harvard wrote 1956.

“The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.” Miller had discovered that our ability to process information and make decisions in the world is limited by a fundamental constraint: We can only think about roughly seven things at a time.

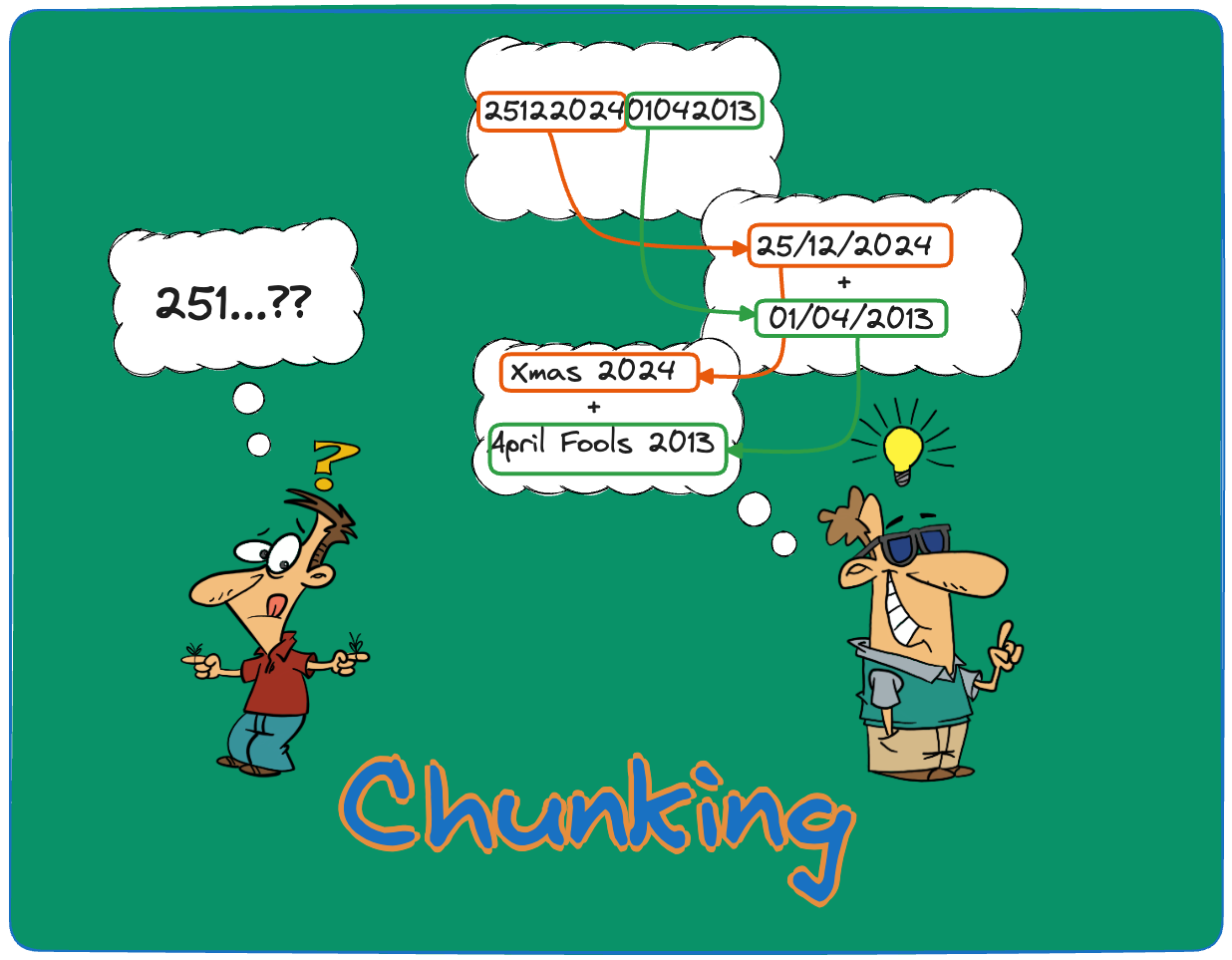

Chunking

The process of chunking takes seemingly meaningless information and reinterprets it in light of information that is already stored away somewhere in our long-term memory. If you didn’t know the dates of Pearl Harbor or September 11, you’d never be able to chunk that twelve-digit numerical string. If you spoke Swahili and not English, the nursery rhyme would remain a jumble of letters. In other words, when it comes to chunking—and to our memory more broadly—what we already know determines what we’re able to learn.

Chess players pattern recognition skills

What separates merely good chess players from those who are world-class? Did the best-class players see more moves ahead? Did they ponder more possible moves? Did they have better tools for analyzing those moves? Did they simply have a better intuitive grasp of the dynamics of the game?

What De Groot uncovered was an even bigger surprise than what his Russian predecessors had found. For the most part, the chess experts didn’t look more moves ahead, at least not at first. They didn’t even consider more possible moves. Rather, they behaved in a manner surprisingly similar to the chicken sexers: They tended to see the right moves, and they tended to see them almost right away.

They talked about configurations of pieces like “pawn structures” and immediately noticed things that were out of sorts, like exposed rooks. They weren’t seeing the board as thirty-two pieces. They were seeing it as chunks of pieces, and systems of tension.

Grand masters literally see a different board. Studies of their eye movements have found that they look at the edges of squares more than inexperienced players, suggesting that they’re absorbing information from multiple squares at once. Their eyes also dart across greater distances, and linger for less time at any one place. They focus on fewer different spots on the board, and those spots are more likely to be relevant to figuring out the right move.

We don’t remember isolated facts; we remember things in context. A board of randomly arranged chess pieces has no context—there are no similar boards to compare it to, no past games that it resembles, no ways to meaningfully chunk it. Even to the world’s best chess player it is, in essence, noise.

4 - The most forgetful man in the world

Story of a person with two types of amnesia—anterograde, which means he can’t form new memories, and retrograde, which means he can’t recall old memories either, at least not since about 1950.

Without time, there would be no need for a memory. But without a memory, would there be such a thing as time? I don’t mean time in the sense that, say, physicists speak of it: the fourth dimension, the independent variable, the quantity that compresses when you approach the speed of light. I mean psychological time, the tempo at which we experience life’s passage. Time as a mental construct.

It’s a point well illustrated by Michel Siffre, a French chronobiologist (he studies the relationship between time and living organisms) who conducted one of the most extraordinary acts of self-experimentation in the history of science. In 1962, Siffre spent two months living in total isolation in a subterranean cave, without access to clock, calendar, or sun. Sleeping and eating only when his body told him to, he sought to discover how the natural rhythms of human life would be affected by living “beyond time.”

Very quickly Siffre’s memory deteriorated. In the dreary darkness, his days melded into one another and became one continuous, indistinguishable blob. Since there was nobody to talk to, and not much to do, there was nothing novel to impress itself upon his memory. There were no chronological landmarks by which he could measure the passage of time. At some point he stopped being able to remember what happened even the day before. His experience in isolation had turned him into EP. As time began to blur, he became effectively amnesic. Soon, his sleep patterns disintegrated. Some days he’d stay awake for thirty-six straight hours, other days for eight—without being able to tell the difference. When his support team on the surface finally called down to him on September 14, the day his experiment was scheduled to wrap up, it was only August 20 in his journal. He thought only a month had gone by. His experience of time’s passage had compressed by a factor of two.

Monotony collapses time; novelty unfolds it. You can exercise daily and eat healthily and live a long life, while experiencing a short one. If you spend your life sitting in a cubicle and passing papers, one day is bound to blend unmemorably into the next—and disappear. That’s why it’s important to change routines regularly, and take vacations to exotic locales, and have as many new experiences as possible that can serve to anchor our memories. Creating new memories stretches out psychological time, and lengthens our perception of our lives.

One well-supported hypothesis holds that our memories are nomadic. While the hippocampus is involved in their initial formation, their contents are ultimately held in long-term storage in the neocortex. Over time, as they are revisited and reinforced, memories are consolidated in a way that makes them impervious to erasure. They become entrenched in a network of cortical connections that allows them to exist independently of the hippocampus.

5 - The memory palace

The principle underlying all memory techniques is that our brains don’t remember all types of information equally well. As exceptional as we are at remembering visual imagery (think of the two-picture recognition test), we’re terrible at remembering other kinds of information, like lists of words or numbers. The point of memory techniques is to do what the synasthete S did instinctually: to take the kinds of memories our brains aren’t good at holding on to and transform them into the kinds of memories our brains were built for.

“The general idea with most memory techniques is to change whatever boring thing is being inputted into your memory into something that is so colorful, so exciting, and so different from anything you’ve seen before that you can’t possibly forget it,”

That proud tradition began, at least according to legend, in the fifth century B.C. with the poet Simonides of Ceos standing in the rubble of the great banquet hall collapse in Thessaly. As the poet closed his eyes and reconstructed the crumbled building in his imagination, he had an extraordinary realization: He remembered where each of the guests at the ill-fated dinner had been sitting. Even though he had made no conscious effort to memorize the layout of the room, it had nevertheless left a durable impression upon his memory. From that simple observation, Simonides reputedly invented a technique that would form the basis of what came to be known as the art of memory. He realized that if it hadn’t been guests sitting at the banquet table, but rather something else—say, every great Greek dramatist seated in order of their dates of birth—he would have remembered that instead. Or what if, instead of banquet guests, he saw each of the words of one of his poems arrayed around the table? Or every task he needed to accomplish that day? Just about anything that could be imagined, he reckoned, could be imprinted upon one’s memory, and kept in good order, simply by engaging one’s spatial memory in the act of remembering. To use Simonides’ technique, all one has to do is convert something unmemorable, like a string of numbers or a deck of cards or a shopping list or Paradise Lost, into a series of engrossing visual images and mentally arrange them within an imagined space, and suddenly those forgettable items become unforgettable.

Virtually all the nitty-gritty details we have about classical memory training—indeed, nearly all the memory tricks in the mental athlete’s arsenal—were first described in a short, anonymously authored Latin rhetoric textbook called the Rhetorica ad Herennium, written sometime between 86 and 82 B.C. It is the only truly complete discussion of the memory techniques invented by Simonides to have survived into the Middle Ages. Though the intervening two thousand years have seen quite a few innovations in the art of memory, the basic techniques have remained fundamentally unchanged from those described in the Ad Herennium. “This book is our bible,” Ed told me.

6 - How to memorize a poem

The earliest memory treatises described two types of recollection: memoria rerum and memoria verborum, memory for things and memory for words.

Cicero agreed that the best way to memorize a speech is point by point, not word by word, by employing memoria rerum. In his De Oratore, he suggests that an orator delivering a speech should make one image for each major topic he wants to cover, and place each of those images at a locus. Indeed, the word “topic” comes from the Greek word topos, or place. (The phrase “in the first place” is a vestige from the art of memory.)

Professional memorizers have existed in oral cultures throughout the world to transmit that heritage through the generations. In India, an entire class of priests was charged with memorizing the Vedas with perfect fidelity. In pre-Islamic Arabia, people known as Rawis were often attached to poets as official memorizers. The Buddha’s teachings were passed down in an unbroken chain of oral tradition for four centuries until they were committed to writing in Sri Lanka in the first century B.C. And for centuries, a group of hired tape recorders called tannaim (literally, “reciters”) memorized the oral law on behalf of the Jewish community.

7 - The end of remembering

Seventy-three-year-old computer scientist at Microsoft named Gordon Bell. Bell sees himself as the vanguard of a new movement that takes the externalization of memory to its logical extreme: a final escape from the biology of remembering.

He registers his whole life with detail every day and stores it digitally.

“Each day that passes I forget more and remember less,” writes Bell in his book Total Recall: How the E-Memory Revolution Will Change Everything. “What if you could overcome this fate? What if you never had to forget anything, but had complete control over what you remembered—and when?”

For the last decade, Bell has kept a digital “surrogate memory” to supplement the one in his brain. It ensures that a record is kept of anything and everything that might be forgotten. A miniature digital camera, called a SenseCam, dangles around his neck and records every sight that passes before his eyes. A digital recorder captures every sound he hears. Every phone call placed through his landline gets taped and every piece of paper Bell reads is immediately scanned into his computer. Bell, who is completely bald, often smiling, and wears rectangular glasses and a black turtleneck, calls this process of obsessive archiving “lifelogging.”

All this obsessive recording may seem strange, but thanks to the plummeting price of digital storage, the increasing ubiquity of digital sensors, and better artificial intelligence to sort through the mess of data we’re constantly collecting, it’s becoming easier and easier to capture and remember ever more information from the world around us. We may never walk around with cameras dangling from our necks, but Bell’s vision of a future in which computers remember everything that happens to us is not nearly as absurd as it might at first sound.

Bell made his name and fortune as an early computing pioneer at the Digital Equipment Corporation in the 1960s and ’70s. (He’s been called the “Frank Lloyd Wright of computers.”) He’s an engineer by nature, which means he sees problems and tries to build solutions. With the SenseCam, he is trying to fix an elemental human problem: that we forget our lives almost as fast as we live them. But why should any memory fade when there are technological solutions that can preserve it?

In 1998, with the help of his assistant Vicki Rozyki, Bell began backfilling his lifelog by systematically scanning every document in the dozens of banker boxes he’d amassed since the 1950s. All of his old photos, engineering notebooks, and papers were digitized. Even the logos on his T-shirts couldn’t escape the scanner bed. Bell, who had always been a meticulous preservationist, figures he’s probably scanned and thrown away three quarters of all the stuff he’s ever owned. Today his lifelog takes up 170 gigabytes, and is growing at the rate of about a gigabyte each month. It includes over 100,000 e-mails, 65,000 photos, 100,000 documents, and 2,000 phone calls. It fits comfortably on a hundred-dollar hard drive.

We Westerners tend to think of the “self,” the elusive essence of who we are, as if it were some starkly delimited entity. Even if modern cognitive neuroscience has rejected the old Cartesian idea of a homuncular soul that resides in the pineal gland and controls the human body, most of us still believe there is a distinct “me” somewhere up there driving the bus. In fact, what we think of as “me” is almost certainly something far more diffuse and hazier than it’s comfortable to contemplate. At the least, most people assume that their self could not possibly extend beyond the boundaries of their epidermis into books, computers, a lifelog. But why should that be the case? Our memories, the essence of our selfhood, are actually bound up in a whole lot more than the neurons in our brain. At least as far back as Socrates’s diatribe against writing, our memories have always extended beyond our brains and into other storage containers. Bell’s lifelogging project simply brings that truth into focus.

This connects to the notions in The Extended Mind by Annie Murphy Paul

8 - The ok plateau

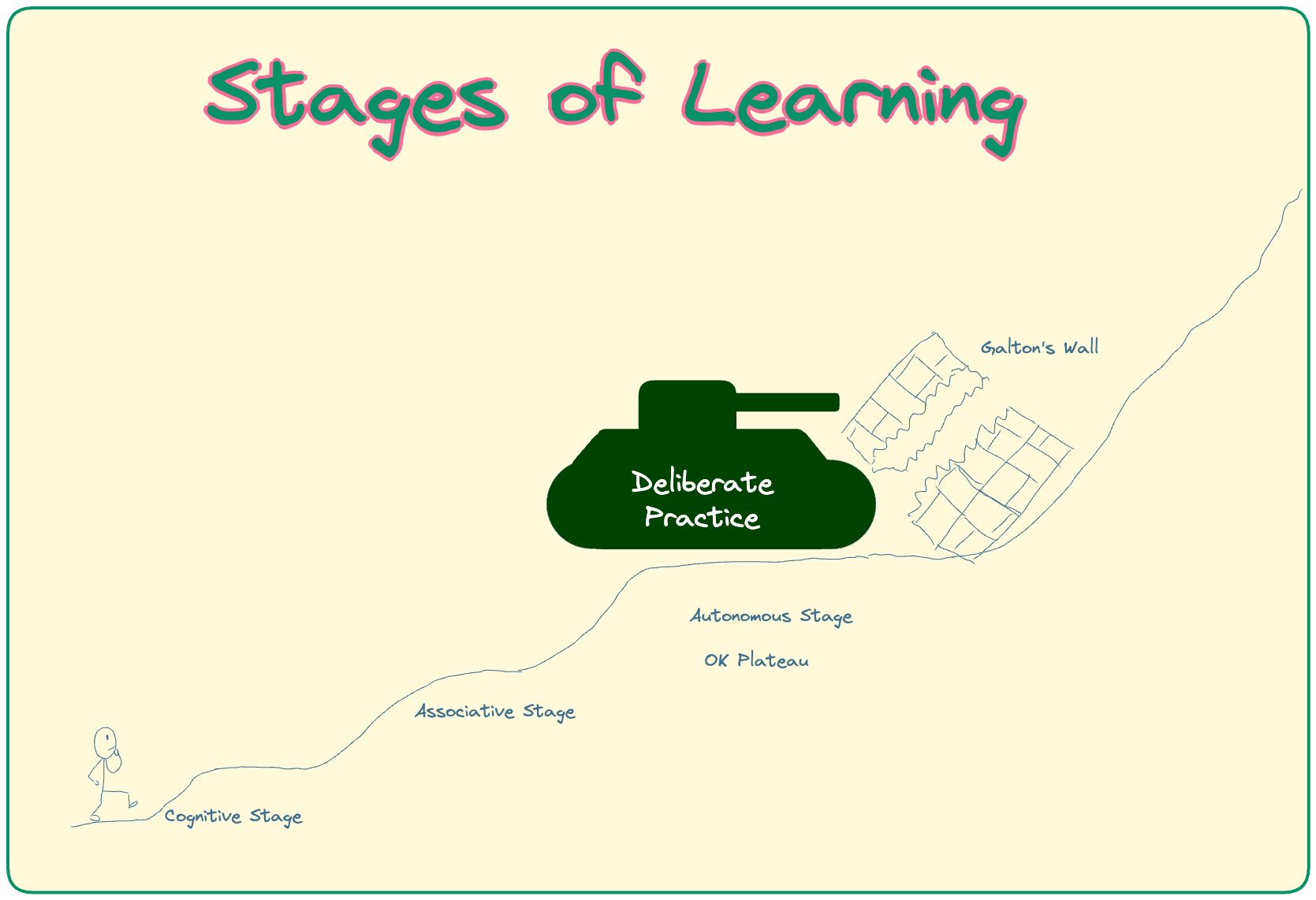

In the 1960s, the psychologists Paul Fitts and Michael Posner

How do we acquire a new skill?

- “cognitive stage,” you’re intellectualizing the task and discovering new strategies to accomplish it more proficiently.

- “associative stage,” you’re concentrating less, making fewer major errors, and generally becoming more efficient.

- “autonomous stage,” when you figure that you’ve gotten as good as you need to get at the task and you’re basically running on autopilot.

During that autonomous stage, you lose conscious control over what you’re doing. Most of the time that’s a good thing. Your mind has one less thing to worry about. In fact, the autonomous stage seems to be one of those handy features that evolution worked out for our benefit. The less you have to focus on the repetitive tasks of everyday life, the more you can concentrate on the stuff that really matters, the stuff that you haven’t seen before. And so, once we’re just good enough at typing, we move it to the back of our mind’s filing cabinet and stop paying it any attention. You can actually see this shift take place in fMRI scans of people learning new skills.

Ok Plateau

As a task becomes automated, the parts of the brain involved in conscious reasoning become less active and other parts of the brain take over. You could call it the “OK plateau,” the point at which you decide you’re OK with how good you are at something, turn on autopilot, and stop improving.

We all reach OK plateaus in most things we do. We learn how to drive when we’re in our teens and then once we’re good enough to avoid tickets and major accidents, we get only incrementally better. My father has been playing golf for forty years, and he’s still—though it will hurt him to read this—a duffer. In four decades his handicap hasn’t fallen even a point. How come? He reached an OK plateau.

Galton Wall

Psychologists used to think that OK plateaus marked the upper bounds of innate ability. In his 1869 book Hereditary Genius, Sir Francis Galton argued that a person could only improve at physical and mental activities up until he reached a certain wall, which “he cannot by any education or exertion overpass.” According to this view, the best we can do is simply the best we can do.

But Ericsson and his fellow expert performance psychologists have found over and over again that with the right kind of concerted effort, that’s rarely the case. They believe that Galton’s wall often has much less to do with our innate limits than simply with what we consider an acceptable level of performance.

Deliberate practice

What separates experts from the rest of us is that they tend to engage in a very directed, highly focused routine, which Ericsson has labeled “deliberate practice.”

Experts consciously keep out of the autonomous stage while they practice by doing three things:

- focusing on their technique,

- staying goal-oriented, and

- getting constant and immediate feedback on their performance.

In other words, they force themselves to stay in the “cognitive phase.”

Amateur musicians - practice time playing music,

pros - work through tedious exercises or focus on specific, difficult parts of pieces.

The best ice skaters spend more of their practice time trying jumps that they land less often, while lesser skaters work more on jumps they’ve already mastered. Deliberate practice, by its nature, must be hard.

When you want to get good at something, how you spend your time practicing is far more important than the amount of time you spend.

Regular practice simply isn’t enough. To improve, we must watch ourselves fail, and learn from our mistakes.

The best way to get out of the autonomous stage and off the OK plateau, Ericsson has found, is to actually practice failing.

One way to do that is to put yourself in the mind of someone far more competent at the task you’re trying to master, and try to figure out how that person works through problems. Benjamin Franklin was apparently an early practitioner of this technique. In his autobiography, he describes how he used to read essays by the great thinkers and try to reconstruct the author’s arguments according to Franklin’s own logic. He’d then open up the essay and compare his reconstruction to the original words to see how his own chain of thinking stacked up against the master’s. The best chess players follow a similar strategy. They will often spend several hours a day replaying the games of grand masters one move at a time, trying to understand the expert’s thinking at each step. Indeed, the single best predictor of an individual’s chess skill is not the amount of chess he’s played against opponents, but rather the amount of time he’s spent sitting alone working through old games.

The secret to improving at a skill is to retain some degree of conscious control over it while practicing—to force oneself to stay out of autopilot. With typing, it’s relatively easy to get past the OK plateau. Psychologists have discovered that the most efficient method is to force yourself to type faster than feels comfortable, and to allow yourself to make mistakes. In one noted experiment, typists were repeatedly flashed words 10 to 15 percent faster than their fingers were able to translate them onto the keyboard. At first they weren’t able to keep up, but over a period of days they figured out the obstacles that were slowing them down, and overcame them, and then continued to type at the faster speed. By bringing typing out of the autonomous stage and back under their conscious control, they had conquered the OK plateau.

9 - The talented tenth

Moniker used to describe the 10 students that compose the U.S. Memory Championship Team. This comes from W. E. B. Du Bois’s notion that an elite corps of African-Americans would lift the race out of poverty.

Memorization started being removed from school curriculum because it was considered dehumanizing and pitting students to repeating robots.

Into this void rushed a group of progressive educators led by the American philosopher John Dewey, who began making the case for a new kind of education that would radically break with the constricted curriculum and methods of the past. They echoed Rousseau’s romantic ideals of childhood, and put a new emphasis on “child centered” education. They did away with rote memorization and replaced it with a new kind of “experiential learning.” Students would study biology not by memorizing plant anatomy from a textbook but by planting seeds and tending gardens. They’d learn arithmetic not through times tables but through baking recipes. Dewey declared, “I would have a child say not, ‘I know,’ but ‘I have experienced.’ ”

The last century has been an especially bad one for memory. A hundred years of progressive education reform have discredited memorization as oppressive and stultifying—not only a waste of time, but positively harmful to the developing brain. Schools have deemphasized raw knowledge (most of which gets forgotten anyway), and instead stressed their role in fostering reasoning ability, creativity, and independent thinking.

“Memory needs to be taught as a skill in exactly the same way that flexibility and strength and stamina are taught to build up a person’s physical health and well being,” argues Buzan, who often sounds like an advocate of the old faculty psychology. “Students need to learn how to learn. First you teach them how to learn, then you teach them what to learn.

“The formal education system came out of the military, where the least educated and most educationally deprived people were sent into the army,” he says. “In order for them not to think, which is what you wanted them to do, they had to obey orders. Military training was extremely regimented and linear. You pounded the information into their brains and made them respond in a Pavlovian manner without thinking. Did it work? Yes. Did they enjoy the experience? No, they didn’t. When the industrial revolution came, soldiers were needed on the machines, and so the military approach to education was transferred into school. It worked. But it doesn’t work over the long term.”

Like many of Buzan’s pontifications, this one conceals a kernel of truth beneath an overlay of propaganda. Rote learning—the old “drill and kill” method that education reformers have spent the last century rebelling against—is surely as old as learning itself, but Buzan is right that the art of memory, once at the center of a classical education, had all but disappeared by the nineteenth century.

Buzan’s argument that schools have been teaching memory in entirely the wrong way deeply challenges reigning ideas in education, and is often couched in the language of revolution. In fact, though Buzan doesn’t seem to see it this way, his ideas are not revolutionary so much as deeply conservative. His goal is to turn the clock back to a time when a good memory still counted for something.

Memory and Creativity are closely related

The notion that memory and creativity are two sides of the same coin sounds counterintuitive. Remembering and creativity seem like opposite, not complementary, processes. But the idea that they are one and the same is actually quite old, and was once even taken for granted. The Latin root inventio is the basis of two words in our modern English vocabulary: inventory and invention.

Memory - - - Creativity

Inventory - - - Invention

And to a mind trained in the art of memory, those two ideas were closely linked. Invention was a product of inventorying. Where do new ideas come from if not some alchemical blending of old ideas? In order to invent, one first needed a proper inventory, a bank of existing ideas to draw on. Not just an inventory, but an indexed inventory. One needed a way of finding just the right piece of information at just the right moment.

Buzan is a little pseudosciency and tends to focus more on marketing claims than real science backed claims.

Mind Mapping

My own impression of Mind Mapping, having tried the technique to outline a few parts of this book, is that much of its usefulness comes from the mindfulness necessary to create the map. Unlike standard note-taking, you can’t Mind Map on autopilot. My sense is that it’s a reasonably efficient way to brainstorm and organize information, but hardly the “ultimate mind-power tool” or “revolutionary system” that Buzan makes it out to be.

10 - The little rain man in all of us

In reference to the movie Rain Man (1988) - IMDb in which the Character Raymond Babbit (played by Dustin Hoffman) inherits a fortune and his brother Charlie Babbit (Tom Cruise) tries to approach Raymond to get access to the fortune. Raymond is autistic and in the process of getting closer to him, Charlie finds out his extraordinary abilities due to his deeply rooted autism.

Asperger Syndrome

Daniel’s other rare condition is Asperger’s syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism. Autism was first identified in 1943 by the child psychiatrist Leo Kanner. He described it as a form of social impairment, a disorder in which, as Kanner put it, patients “treat people as if they were things.” Along with this inability to empathize, autistic individuals have a host of other problems, including language impairment, an extremely focused range of interests, and “an anxiously obsessive desire for the preservation of sameness.” A year after Kanner first wrote about autism, an Austrian pediatrician named Hans Asperger noted another disorder that seemed almost identical except that Asperger’s patients had strong linguistic abilities and fewer intellectual impairments. He called his precocious young patients, with their bottomless wells of arcane trivia, “little professors.” It wasn’t until 1981 that Asperger’s was recognized as its own separate syndrome.

We all have remarkable capabilities asleep inside of us. If only we bothered to awaken them.

11 - The US memory championships.

Joshua wins the U.S. memory Championship.

So had I improved my memory? By every objective measure, I had improved something. My digit span, the gold standard by which working memory is measured, had doubled from nine to eighteen. Compared with my tests almost a year earlier, I could recall more lines of poetry, more people’s names, more pieces of random information thrown my way. And yet a few nights after the world championship, I went out to dinner with a couple of friends, took the subway home, and only remembered as I was walking in the door to my parents’ house that I’d driven a car to dinner. I hadn’t just forgotten where I parked it. I’d forgotten I had it.

That was the paradox: For all of the memory stunts I could now perform, I was still stuck with the same old shoddy memory that misplaced car keys and cars. Even while I had greatly expanded my powers of recall for the kinds of structured information that could be crammed into a memory palace, most of the things I wanted to remember in my everyday life were not facts or figures or poems or playing cards or binary digits. Yes, I could memorize the names of dozens of people at a cocktail party, and that was surely useful. And you could give me a family tree of English monarchs, or the terms of the American secretaries of the interior, or the dates of every major battle in World War II, and I could learn that information relatively fast, and even hold on to it for a while. These skills would have been a godsend in high school. But life, for better or worse, only occasionally resembles high school.

While my digit span may have doubled, could it really be said that my working memory was twice as good as it had been when I started my training? I wish I could say it was. But the truth is, it wasn’t. When asked to recall the order of, say, a series of random inkblots or a series of color swatches or the clearance of the doorway to my parents’ cellar, I was no better than average. My working memory was still limited by the same magical number seven that constrains everyone else. Any kind of information that couldn’t be neatly converted into an image and dropped into a memory palace was just as hard for me to retain as it had always been. I’d upgraded my memory’s software, but my hardware seemed to have remained fundamentally unchanged.

📋 Table of Contents

- The smartest man is hard to find

- The man who remembered too much

- The most forgetful man in the world

- The expert expert

- The memory palace

- How to memorize a poem

- The end of remembering

- The ok plateau

- The talented tenth

- The little rain man in all of us

- The US memory championships.

🥩 Raw Notes

CHARACTER BUILDING

Memory training was considered a form of character building, a way of developing the cardinal virtue of prudence and ethics.

Only through memorizing could ideas truly be incorporated into one’s psyche and their values absorbed.

Memorization techniques existed to etch foundational texts and ideas into the brain. A strong memory was seen as the greatest virtue since it represented the internalization of a universe of external knowledge.

Memory training is a form of mental workout. Over time, like any form of exercise, it’ll make the brain fitter, quicker, and more nimble.

Roman orators argued that the art of memory - the proper retention and ordering of knowledge - was a vital instrument for the invention of new ideas.

A trained memory wasn’t just about gaining easy access to information; it was about strengthening one’s personal ethics and becoming a more complete person.

A trained memory was the key to cultivating “judgment, citizenship, and piety.”

Schools go about teaching all wrong. They pour vast amounts of information into students’ heads, but don’t teach them how to retain it.

What one memorized helped shape one’s character.

Where could one look for guidance about how to act, if not the depths of memory?

The ancient and medieval way of reading was totally different from how we read today. One didn’t just memorize texts; one ruminated on them - chewed them up and regurgitated them like cud - and in the process, became intimate with them in a way that made them one’s own.

Who are you going to be more impressed by, the person who has a litany of his own opinions, or the historian who can draw on the great thinkers who came before him?

The people whose intellects I most admire always seem to have a fitting anecdote or germane fact at the ready. They’re able to reach out across the breadth of their learning and pluck from distant patches.

ATTENTION

What I had really trained my brain to do, as much as to memorize, was to be more mindful, and to pay attention to the world around me. Remembering can only happen if you decide to take notice.

When we forget the name of a new acquaintance, it’s because we’re too busy thinking about what we’re going to say next, instead of paying attention. Part of the reason techniques like visual imagery and the memory palace work so well is that they enforce a degree of attention and mindfulness that is normally lacking. You can’t create an image of a word, a number, or a person’s name without dwelling on it. And you can’t dwell on something without making it more memorable.

From the vast amounts of data pouring in through the senses, our brains must quickly sift out which information is likely to have some bearing on the future, attend to that, and ignore the noise.

EXPERTISE

On every single test of general cognitive ability, the mental athletes’ scores came back well within the normal range. The memory champs weren’t smarter, and they didn’t have special brains.

When the mental athletes were learning new information, they were engaging several regions of the brain known to be involved in two specific tasks: visual memory and spatial navigation.

Experts see the world differently. They notice things that nonexperts don’t see. They home in on the information that matters most, and have an almost automatic sense of what to do with it. And most important, experts process the enormous amounts of information flowing through their senses in more sophisticated ways.

If every sensation or thought was immediately filed away in the enormous database that is our long-term memory, we’d be drowning in irrelevant information. Most of the things that pass through our brain don’t need to be remembered any longer than the moment or two we spend perceiving them.

Like a computer, our ability to operate in the world, is limited by the amount of information we can juggle at one time. Unless we repeat things over and over, they tend to slip from our grasp.

Repeating them over and over again to themselves in the “phonological loop,” which is just a fancy name for the little voice that we can hear inside our head when we talk to ourselves. The phonological loop acts as an echo, producing a short-term memory buffer that can store sounds for just a couple seconds.

Chunking is a way to decrease the number of items you have to remember by increasing the size of each item.

What we already know determines what we’re able to learn.

Chunking takes seemingly meaningless information and reinterprets it in light of information that is already stored away somewhere in our long-term memory.

All experts use their memories to see the world differently. Over many years, they build up a bank of experience that shapes how they perceive new information.

Chess experts tended to see the right moves almost right away. It was as if the chess experts weren’t thinking so much as reacting.

They talked about configurations of pieces like “pawn structures” and immediately noticed things that were out of sorts, like exposed rooks. They weren’t seeing the board as thirty-two pieces. They were seeing it as chunks of pieces, and systems of tension.

A telling fact about memory, and about expertise in general: We don’t remember isolated facts; we remember things in context.

Contrary to all the old wisdom that chess is an intellectual activity based on analysis, many of the chess master’s important decisions about which moves to make happen in the immediate act of perceiving the board.

Higher-rated chess players are recalling information from long-term memory. Lower-ranked players are encoding new information.

The experts are interpreting the present board in term of their massive knowledge of past ones. The lower-ranked players are seeing the board as something new.

What we call expertise is really just “vast amounts of knowledge, pattern-based retrieval, and planning mechanisms acquired over many years of experience in the associated domain.”

In other words, a great memory isn’t just a by-product of expertise; it is the essence of expertise.

OK PLATEAU / DELIBERATE PRACTICE

Many people sit behind a keyboard for at least several hours a day in essence practicing their typing. Why don’t they just keep getting better and better?

Three stages that anyone goes through when acquiring a new skill.

- “cognitive stage” you’re intellectualizing the task and discovering new strategies to accomplish it more proficiently.

- “associative stage,” you’re concentrating less, making fewer major errors, and generally becoming more efficient.

- “autonomous stage,” when you figure that you’ve gotten as good as you need to get at the task and you’re basically running on autopilot.

During that autonomous stage, you lose conscious control over what you’re doing. Most of the time that’s a good thing. Your mind has one less thing to worry about.

Call it the “OK plateau,” the point at which you decide you’re OK with how good you are at something, turn on autopilot, and stop improving.

What separates experts from the rest of us is that they tend to engage in a very directed, highly focused routine, which Ericsson has labeled “deliberate practice.”

Consciously keeping out of the autonomous stage while they practice by doing three things: focusing on their technique, staying goal-oriented, and getting constant and immediate feedback on their performance. In other words, they force themselves to stay in the “cognitive phase.”

Unless he’s consciously challenging himself and monitoring his performance - reviewing, responding, rethinking, rejiggering - it’s never going to make him appreciably better.

Regular practice simply isn’t enough. To improve, we must watch ourselves fail, and learn from our mistakes.

The best way to get out of the autonomous stage and off the OK plateau is to actually practice failing.

One way to do that is to put yourself in the mind of someone far more competent at the task you’re trying to master, and try to figure out how that person works through problems.

The single best predictor of an individual’s chess skill is not the amount of chess he’s played against opponents, but rather the amount of time he’s spent sitting alone working through old games.

Force yourself to type faster than feels comfortable, and to allow yourself to make mistakes.

Typists were repeatedly flashed words 10 to 15 percent faster than their fingers were able to translate them onto the keyboard. At first they weren’t able to keep up, but over a period of days they figured out the obstacles that were slowing them down, and overcame them, and then continued to type at the faster speed.

Ericsson suggested I try the same thing with cards. He told me to find a metronome and to try to memorize a card every time it clicked. Once I figured out my limits, he instructed me to set the metronome 10 to 20 percent faster than that and keep trying at the quicker pace until I stopped making mistakes. Whenever I came across a card that was particularly troublesome, I was supposed to make a note of it, and see if I could figure out why it was giving me problems. It worked, and within a couple days I was off the OK plateau and my card times began falling again at a steady clip. If they’re not practicing deliberately, even experts can see their skills backslide.

My practice would have to be focused and deliberate. That meant I needed to collect data and analyze it for feedback. And that meant this whole operation was about to get ratcheted up.

Practice makes perfect. But only if it’s the right kind of concentrated, self-conscious, deliberate practice. I’d learned firsthand that with focus, motivation, and, above all, time, the mind can be trained to do extraordinary things.

CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION

Learning, memory, and creativity are the same fundamental process directed with a different focus.

The art and science of memory is about developing the capacity to quickly create images that link disparate ideas.

Creativity is the ability to form similar connections between disparate images and to create something new and hurl it into the future so it becomes a poem, or a building, or a dance, or a novel.

Creativity is, in a sense, future memory.

If the essence of creativity is linking disparate facts and ideas, then the more facility you have making associations, and the more facts and ideas you have at your disposal, the better you’ll be at coming up with new ideas.

Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, was the mother of the Muses.

Latin root inventio is the basis of two words in our modern English vocabulary: inventory and invention.

In order to invent, one first needed a proper inventory, a bank of existing ideas to draw on. Not just an inventory, but an indexed inventory. One needed a way of finding just the right piece of information at just the right moment. This is what the art of memory was ultimately most useful for. It was not merely a tool for recording but also a tool of invention and composition.

When information goes “in one ear and out the other,” it’s often because it doesn’t have anything to stick to.

The people whose intellects I most admire always seem to have a fitting anecdote or germane fact at the ready. They’re able to reach out across the breadth of their learning and pluck from distant patches.

People who have more associations to hang their memories on are more likely to remember new things, which in turn means they will know more, and be able to learn more. The more we remember, the better we are at processing the world.

LANDMARKS AND NOVELTY IN LIFE

The idea is to avoid that feeling you have when you get to the end of the year and feel like, where the hell did that go?

How to do it? By remembering more. By providing life with more chronological landmarks. By making yourself more aware of time’s passage.

The more we pack our lives with memories, the slower time seems to fly.

Monotony collapses time; novelty unfolds it.

You can exercise daily and eat healthily and live a long life, while experiencing a short one.

If you spend your life sitting in a cubicle and passing papers, one day is bound to blend unmemorably into the next - and disappear.

That’s why it’s important to change routines regularly, and take vacations to exotic locales, and have as many new experiences as possible that can serve to anchor our memories.

Creating new memories stretches out psychological time, and lengthens our perception of our lives.

In youth we may have an absolutely new experience, subjective or objective, every hour of the day.

Life seems to speed up as we get older because life gets less memorable.

Of all the things one could be obsessive about collecting, memories of one’s own life don’t seem like the most unreasonable. There’s something even strangely rational about it.

Socrates thought the unexamined life was not worth living. How much more so the unremembered life?

The elaborate system of externalized memory we’ve created is a way of fending off mortality.

Siffre spent two months living in total isolation in a subterranean cave, without access to clock, calendar, or sun. Sleeping and eating only when his body told him to, he sought to discover how the natural rhythms of human life would be affected by living “beyond time.” Very quickly Siffre’s memory deteriorated. In the dreary darkness, his days melded into one another and became one continuous, indistinguishable blob. Since there was nobody to talk to, and not much to do, there was nothing novel to impress itself upon his memory. There were no chronological landmarks by which he could measure the passage of time. At some point he stopped being able to remember what happened even the day before.

PERMANENCE

Each time we think about a memory, we integrate it more deeply into our web of other memories, and therefore make it more stable and less likely to be dislodged.

Older memories are often remembered as if captured by a third person holding a camera, whereas more recent events tend to be remembered in the first person, as if through one’s own eyes.

It’s as if things that happened to us become simply things that happened.

Or as if, over time, the brain naturally turns episodes into facts.

Over time, as they are revisited and reinforced, memories are consolidated in a way that makes them impervious to erasure.

The vast majority of us don’t trust our memories. We find shortcuts to avoid relying on them. We complain about them endlessly, and see even their smallest lapses as evidence that they’re starting to fail us entirely.

If something is going to be made memorable, it has to be dwelled upon, repeated.

ASSOCIATIONS

The nonlinear associative nature of our brains makes it impossible for us to consciously search our memories in an orderly way. A memory only pops directly into consciousness if it is cued by some other thought or perception.

Take the kinds of memories our brains aren’t good at holding on to and transform them into the kinds of memories our brains were built for.

Change whatever boring thing is being inputted into your memory into something that is so colorful, so exciting, and so different from anything you’ve seen before that you can’t possibly forget it.

It’s very important to try to remember this image multisensorily. The more associative hooks a new piece of information has, the more securely it gets embedded into the network of things you already know, and the more likely it is to remain in memory.

It’s important that you deeply process that image, so you give it as much attention as possible.

Things that grab our attention are more memorable, and attention is not something you can simply will. It has to be pulled in by the details. By laying down elaborate, engaging, vivid images in your mind, it more or less guarantees that your brain is going to end up storing a robust, dependable memory.

Exaggerate its proportions. The funnier, lewder, and more bizarre, the better.

When we see in everyday life things that are petty, ordinary, and banal, we generally fail to remember them, because the mind is not being stirred by anything novel or marvelous. But if we see or hear something exceptionally base, dishonorable, extraordinary, great, unbelievable, or laughable, that we are likely to remember for a long time.

Create these sorts of lavish images on the fly, to paint in the mind a scene so unlike any that has been seen before that it cannot be forgotten. And to do it quickly.

Particularly interesting, and therefore memorable: jokes and sex.

Animate images tend to be more memorable than inanimate images.

Disfigure them, as by introducing one stained with blood or soiled with mud or smeared with red paint.

He has created his own dictionary of images for each of the two hundred most common words that can’t easily be visualized.

“And” is a circle (“and” rhymes with rund, which means round in German).

“The” is someone walking on his knees (die, a German word for “the,” rhymes with Knie, the German word for “knee”).

When the poem reaches a period, he hammers a nail into that locus.

What do you do with words like “ephemeral” or “self” that are impossible to see?

Gunther’s method of creating an image for the un-imageable is a very old one: to visualize a similarly sounding, or punning, word in its place.

This process of transforming words into images involves a kind of remembering by forgetting: In order to memorize a word by its sound, its meaning has to be completely dismissed.

Many actors will tell you that they break their lines into units they call “beats,” each of which involves some specific intention or goal on the character’s part, which they train themselves to empathize with.

Giving a line more associational hooks to hang on by embedding it in a context of both emotional and physical cues.

The art of memory is learning how little of an image you need to see to make it memorable.

Savor the images, and really enjoy them. So long as you’re surprising yourself with their lively goodness,

MEMORY PALACE

Convert something unmemorable into a series of engrossing visual images and mentally arrange them within an imagined space, and suddenly those forgettable items become unforgettable.

Create a space in the mind’s eye, a place that you know well and can easily visualize, and then populate that imagined place with images representing whatever you want to remember.

He used his own body parts as loci to help him memorize the entire 56,000-word, 1,774-page Oxford Chinese-English dictionary.

Humans are very, very good at learning spaces.

Walking around: Without really noticing it, you’d remember the whereabouts of hundreds of objects and all sorts of dimensions that you wouldn’t even notice yourself noticing. If you actually add up all that information, it’s like the equivalent of a short novel. But we don’t ever register that as being a memory achievement. Humans just gobble up spatial information. The principle of the memory palace is to use one’s exquisite spatial memory to structure and store information whose order comes less naturally.

The crucial thing was to choose a memory palace with which I was intimately familiar.

I first needed a stockpile of memory palaces at my disposal. I went for walks around the neighborhood. I visited friends’ houses, the local playground.

Know these buildings so thoroughly - have such a rich and textured set of associations with every corner of every room - that when it comes time to learn some new body of information, you can speed through your palaces, scattering images as quickly as you can sketch them in your imagination.

The better I knew the buildings, and the more each felt like home, the stickier my images would be, and the easier it would be to reconstruct them later. I’d need about a dozen memory palaces just to begin my training. He has several hundred, a metropolis of mental storehouses.

(The phrase “in the first place” is a vestige from the art of memory.)

ORAL TRADITIONS

The brain best remembers things that are repeated, rhythmic, rhyming, structured, and above all easily visualized.

If you can turn a set of words into a jingle, they can become exceedingly difficult to knock out of your head.

The reason we teach kids the alphabet in a song and not as twenty-six individual letters. Song is the ultimate structuring device for language.

The variability that is built into the poetry of oral traditions allows the bard to adapt the material to the audience, but it also allows more memorable versions of the poem to arise. Folklorists have compared oral poems to pebbles worn down by the water. They’re made smooth over many retellings as the harder-to-remember pieces get chipped away, or made easier to retain and repeat. Irrelevant digressions are forgotten. Long or rare words are avoided.

The original oral performance with its poetry was stripped of functional purpose and relegated to the secondary role of entertainment, one which it always had but which now became its sole purpose.

No longer burdened by the requirements of oral transmission, poetry was free to become art.

We don’t speak with spaces. Where one word ends and another begins is a relatively arbitrary linguistic convention. If you look at a sonographic chart visualizing the sound waves of someone speaking English, it’s practically impossible to tell where the spaces are, which is one of the reasons why it’s proven so difficult to train computers to recognize speech. Without sophisticated artificial intelligence capable of figuring out context, a computer has no way of telling the difference between “The stuffy nose may dim liquor” and “The stuff he knows made him lick her.”

Camillo believed there were images that could encapsulate vast and powerful concepts about the universe, and simply by memorizing those images, one would be able understand the hidden connections underlying everything.

NUMBERS / CARDS

A technique known as the “Major System,” invented around 1648 by Johann Winkelmann: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Major_system

Convert numbers into phonetic sounds. Those sounds can then be turned into words, which can in turn become images for a memory palace.

Memorizing long strings of numbers, “person-action-object,” or, simply, PAO. In the PAO system, every two-digit number from 00 to 99 is represented by a single image of a person performing an action on an object.

Any six-digit number, like say 34-13-79, can then be turned into a single image by combining the person from the first number with the action from the second and the object from the third.

It effectively generates a unique image for every number from 0 to 999,999.

Those associations are entirely arbitrary, and have to be learned in advance, which is to say it takes a lot of remembering just to be able to remember.

Memorize decks of playing cards in much the same way, using a PAO system in which each of the fifty-two cards is associated with its own person/action/object image. This allows any triplet of cards to be combined into a single image, and for a full deck to be condensed into just eighteen unique images.

To be maximally memorable, one’s images have to appeal to one’s own sense of what is colorful and interesting.

Before I could memorize any decks of cards, I first had to memorize those fifty-two images. No minor job.

BRAIN

Memories gradually decay with time along what’s known as the “curve of forgetting.”

From the moment you grasp a new piece of information, your memory’s hold on it begins to slowly loosen, until finally it lets go altogether.

Hermann Ebbinghaus first brought the study of memory into the laboratory in the 1870s. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus set out to quantify this inexorable process of forgetting. In order to understand how our memories fade over time, he spent years memorizing 2,300 three-letter nonsense syllables. At set periods, he would test himself to see how many of the syllables he’d forgotten and how many he’d managed to retain. When he graphed the results, he got a curve that looked like this (falling curve of spaced interfals.) No matter how many times he performed the experiment on himself, the results were always roughly the same: In the first hour after learning a set of nonsense syllables, more than half of them would be forgotten. After the first day, another 10 percent would disappear. After a month, another 14 percent. After that, the memories that were left had more or less stabilized - they had become consolidated in long-term memory - and the pace of forgetting slowed to a gentle creep.

A memory is a pattern of connections between your neurons.

No one has ever actually seen a memory in the human brain.

The brain makes sense up close and from far away. It’s the in-between - the stuff of thought and memory, the language of the brain - that remains a profound mystery.

OTHER

Participatory journalism.

Ed was an aesthete, in the true Oscar Wilde sense. He participated in life as if it were art, and practiced a studied, careful carefreeness. His sense of what is worthy seemed to overlap very little with any conventional sense of what is useful, and if there were one precept that could be said to govern his life, it is that one’s highest calling is to engage in enriching escapades at every turn. He was a genuine bon vivant.

(Amnesiac:) Trapped in this limbo of an eternal present, between a past he can’t remember and a future he can’t contemplate, he lives a sedentary life, completely free from worry. “He’s happy all the time. Very happy. I guess it’s because he doesn’t have any stress in his life.” In his chronic forgetfulness, EP has achieved a kind of pathological enlightenment, a perverted vision of the Buddhist ideal of living entirely in the present.