The Extended Mind - Annie Murphy Paul

📝 Notes

Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain

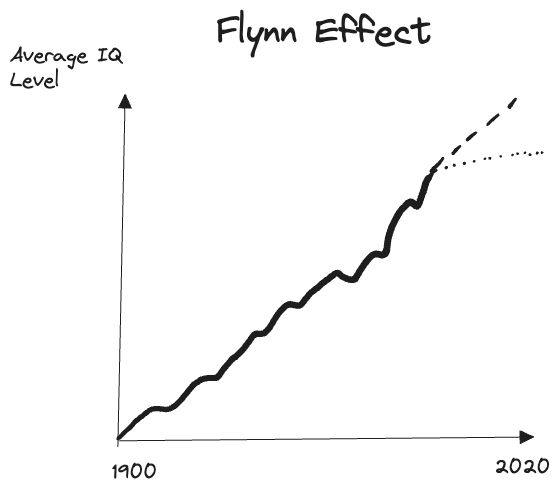

Why have IQ levels been tapering in last year's?

The fact is that we have been putting pressure on our internal brains to evolve while we worsen the external conditions for it to thrive.

Thinking outside the brain means skillfully engaging entities external to our heads

- Embodied cognition - Thinking with our bodies

- Situational cognition - Thinking with our surroundings

- Cooperative cognition - Thinking with others

By reaching beyond the brain to recruit these “extra-neural” resources, we are able to focus more intently, comprehend more deeply, and create more imaginatively—to entertain ideas that would be literally unthinkable by the brain alone.

The human brain is limited in its ability to pay attention, limited in its capacity to remember, limited in its facility with abstract concepts, and limited in its power to persist at a challenging task.

Our approach constitutes an instance of (as the poet William Butler Yeats put it in another context) “the will trying to do the work of the imagination.” The smart move is not to lean ever harder on the brain but to learn to reach beyond it.

Traditional Training

Sit still and use our heads internally. (memorize, internal reasoning, self-discipline, self-motivation)

Missing Training

- Thinking outside our heads, with movement, sensations, gestures.

- How to replenish mental capacity with exposure to nature and outdoors.

- To improve productivity by changing our surroundings.

- To engage in social practices of imitation from experts

- Collective Intelligence is not valued.

The brain is not actually a muscle but rather an organ made up of specialized cells known as neurons.

Brains are like magpies

Our brains, it might be said, are like magpies, fashioning their finished products from the materials around them, weaving the bits and pieces they find into their trains of thought.

- Thought happens not only inside the skull but out in the world, too; it’s an act of continuous assembly and reassembly that draws on resources external to the brain.

- The kinds of materials available to “think with” affect the nature and quality of the thought that can be produced.

- The capacity to think well—that is, to be intelligent—is not a fixed property of the individual but rather a shifting state that is dependent on access to extra-neural resources and the knowledge of how to use them.

Set aside the brain-as-computer and brain-as-muscle metaphors.

David Geary, a professor of psychology at the University of Missouri, makes a useful distinction between “biologically primary” and “biologically secondary” abilities.

The Extended Mind article

Clark and his colleague David Chalmers -> “Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin?”

The mind does not stop at the standard “demarcations of skin and skull,” it is more accurately viewed as “an extended system, a coupling of biological organism and external resources.”

What is an Expert?

Traditional notions of what makes an expert are highly brainbound, focused on internal, individual effort (think of the late psychologist Anders Ericsson’s famous finding that mastery in any field requires “10,000 hours” of practice).

The literature on the extended mind suggests a different view: experts are those who have learned how best to marshal and apply extra-neural resources to the task before them.

Part I: Thinking with Our Bodies

Thinking with Sensations

The size and activity level of the brain’s interoceptive hub, the insula, vary among individuals and are correlated with their awareness of interoceptive sensations.

Interoceptive awareness can be deliberately cultivated.

A series of simple exercises can put us in touch with the messages emanating from within, giving us access to knowledge that we already possess but that is ordinarily excluded from consciousness—knowledge about ourselves, about other people, and about the worlds through which we move.

“Nonconscious information acquisition,” is happening in our lives all the time.

We are always checking for patterns that fit each situation.

This is non-conscious and instant triggered by our Interoceptive faulty.

It's like We have our spider-sense

As we navigate a new situation, we’re scrolling through our mental archive of stored patterns from the past, checking for ones that apply to our current circumstances when a potentially relevant pattern is detected, it’s our interoceptive faculty that tips us off: with a shiver or a sigh, a quickening of the breath or a tensing of the muscles.

Mindfulness meditation is one way of enhancing awareness of non-conscious knowledge triggered by bodily sensations.

By practicing regularly, people usually feel more in touch with sensations in parts of their body they had never felt or thought much about before.

Naming feelings and interoceptive sensations (affect labeling) allows us to begin to regulate them.

Awareness of our interoception can help us become more resilient.

The ability to allocate our internal resources effectively in tackling mental challenges is a capacity researchers call “cognitive resilience.”

“Shuttling”—moving one’s focus back and forth between what is transpiring internally and what is going on outside the body. Balance external events and internal feelings.

—to train ourselves “to pay attention and notice what’s happening while it’s happening,”

the thing we call “emotion” (and experience as a unified whole) is actually constructed from more elemental parts; these parts include the signals generated by the body’s interoceptive system, as well as the beliefs of our families and cultures regarding how these signals are to be interpreted.

Coping and reappraisal approach - Reappraise debilitating “stress” as productive “coping.”

When interacting with other people, we subtly and unconsciously mimic their facial expressions, gestures, posture, and vocal pitch. Then, via the interoception of our own bodies’ signals, we perceive what the other person is feeling because we feel it in ourselves. We bring other people’s feelings onboard, and the body is the bridge.

Thinking with Movement

Scientists have long known that overall physical fitness supports cognitive function; people who have fitter bodies generally have keener minds. 2023-06-25 17:36:28

Doodling increases information retention.

Exercising enhances our capacity to engage in complex cognition.

Another misguided idea about breaks: they should be used to rest the body, so as to fortify us for the next round of mental labor. As we’ve seen, it’s through exerting the body that our brains become ready for the kind of knowledge work so many of us do today. The best preparation for such (metaphorical) acts as wrestling with ideas or running through possibilities is to work up an (actual) sweat.

Instead of languidly sipping a latte before tackling a difficult project, we should be taking an energetic walk around the block.

greatest benefits for thinking detected in the moderate-intensity middle part of exercizing intensity.

I run in order to acquire a void.” Murakami: “transient hypofrontality.”

When all of our resources are devoted to managing the demands of intense physical activity, however, the influence of the prefrontal cortex is temporarily reduced. In this loose hypofrontal mode, ideas and impressions mingle more freely; unusual and unexpected thoughts arise.

Linking movement to the material to be recalled creates a richer and therefore more indelible “memory trace” in the brain. In addition, movements engage a process called procedural memory (memory of how to do something, such as how to ride a bike) that is distinct from declarative memory (memory of informational content, such as the text of a speech). When we connect movement with information, we activate both types of memory, and our recall is more accurate as a result—a phenomenon that researchers call the “enactment effect.”

“Walking (and in a random route) opens up the free flow of ideas,”

Henry David Thoreau. “How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!” he exclaimed. “ the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.”

Thinking with Gesture

psychologist Barbara Tversky

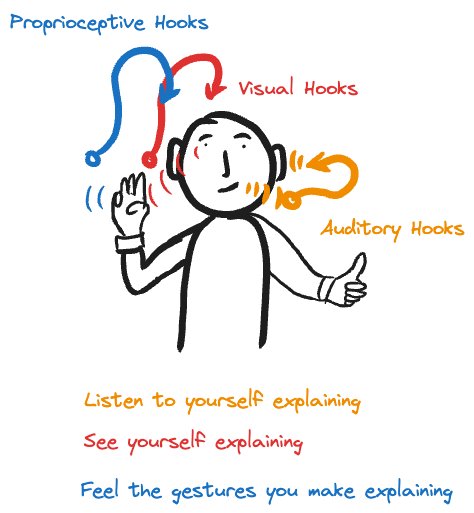

Moving our hands advances our understanding of abstract or complex concepts, reduces our cognitive load, and improves our memory. Making gestures also helps us get our message across to others with more persuasive force.

That’s because gesturing while speaking involves sinking multiple mental “hooks” into the material to be remembered—hooks that enable us to reel in that piece of information when it is needed later on.

- auditory hook: we hear ourselves saying the words aloud.

- visual hook: we see ourselves making the relevant gesture.

- “proprioceptive” hook; this comes from feeling our hands make the gesture.

Part II: Thinking with Our Surroundings

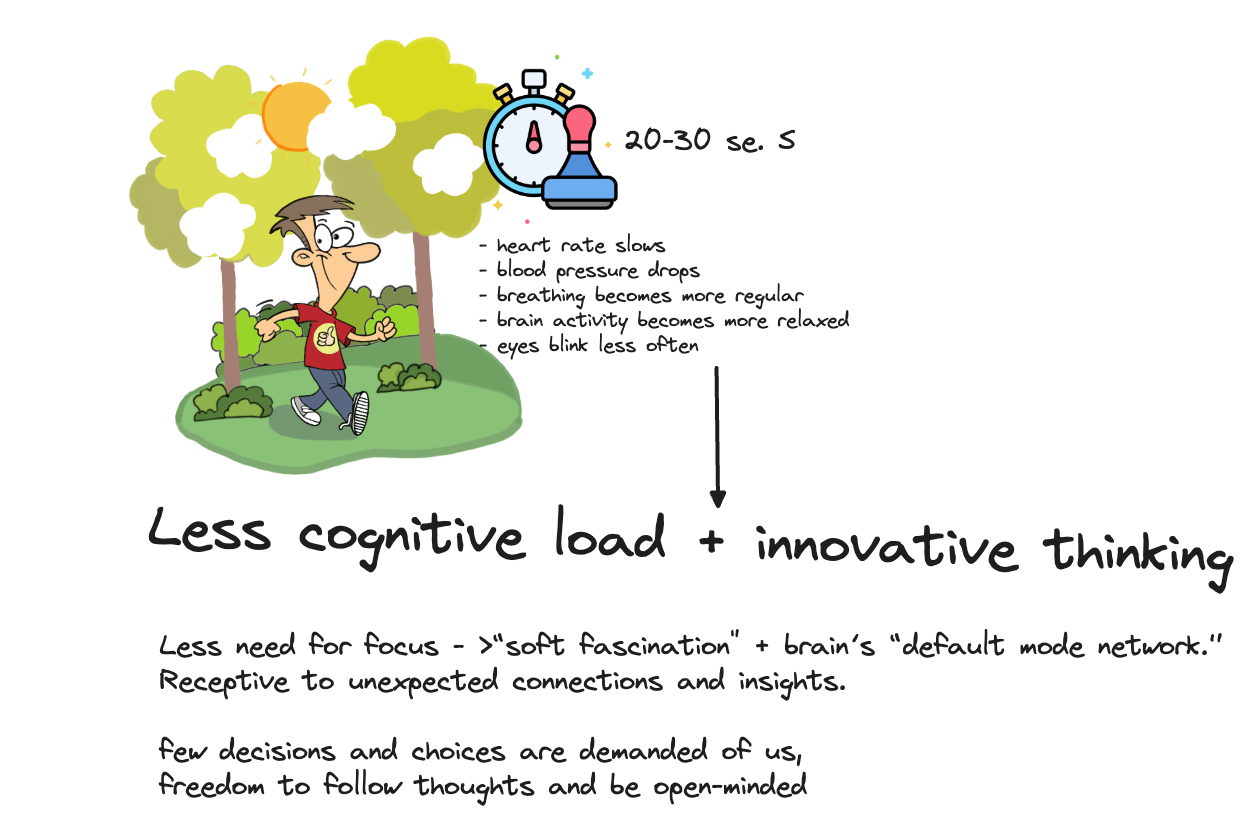

Thinking with Natural Spaces

Drivers who travel along tree-lined roads, for example, recover more quickly from stressful experiences, and handle emerging stresses with more calm, than do people who drive along roads crowded with billboards, buildings, and parking lots.

The sights and sounds of nature help us rebound from stress; they can also help us out of a mental rut. “Rumination” is psychologists’ term for the way we may fruitlessly visit and revisit the same negative thoughts. On our own, we can find it difficult to pull ourselves out of this cycle—but exposure to nature can extend our ability to adopt more productive thought patterns.

There are two kinds of attention, wrote James in his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology: “voluntary” and “passive.”

Voluntary attention takes effort; we must continually direct and redirect our focus as we encounter an onslaught of stimuli or concentrate hard on a task. Navigating an urban environment—with its hard surfaces, sudden movements, and loud, sharp noises—requires voluntary attention.

Passive attention, by contrast, is effortless: diffuse and unfocused, it floats from object to object, topic to topic. This is the kind of attention evoked by nature, with its murmuring sounds and fluid motions; psychologists working in the tradition of James call this state of mind “soft fascination.”

It's not the speed of the journey, it’s what you see along the way.

Even a brief glance out the window can make a difference in our mental capacity.

Seek out such “microrestorative opportunities” throughout the day, replenishing our mental resources with each glance out the window.

Thinking with Built Spaces

“The wall was designed to protect us from the cognitive load of having to keep track of the activities of strangers,” observes Colin Ellard

What about wearing headphones?

Open Work Spaces are bad

Our attention is pulled especially powerfully to the gaze of other people; we are uncannily sensitive to the feeling of being observed. Once we spot others’ eyes on us, the processing of eye contact takes precedence over whatever else our brains were working on.

All this visual monitoring and processing uses up considerable mental resources, leaving that much less brainpower for our work. We know this because of how much better we think when we close our eyes.

Impose the “sensory reduction” that supports optimal attention, memory, and cognition. “Good fences make good neighbours,” wrote poet Robert Frost; likewise, good walls make good collaborators.

Other studies have found that as workspaces become more open, trust and cooperativeness among co-workers declines. The open-plan office seems to discourage exactly the kind of behaviour it was intended to promote.

Solitude is important daily

Monks know the importance of solitude and they enforce it into their timetable through the commitment to twice-daily private prayer, as well as the summum silentium (complete silence, sometimes referred to as ‘the great silence’) at the end of the day.

The ancient arrangement of space in a monastery bears some resemblance to today’s “activity-based workspaces,” which nod to the human need for both social interaction and undisturbed solitude by providing dedicated areas for each: a café-style meeting place, a soundproof study carrel with a door.

Ambient Belonging

When people occupy spaces that they consider their own, they experience themselves as more confident and capable. They are more efficient and productive. They are more focused and less distractible. And they advance their own interests more forcefully and effectively.

In the presence of cues of identity and cues of affiliation, people perform better: they’re more motivated and more productive.

As the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has written, we keep certain objects in view because “they tell us things about ourselves that we need to hear in order to keep our selves from falling apart.”

Moreover, we need to have close at hand those prompts that highlight particular facets of our identity. Each of us has not one identity but many —worker, student, spouse, parent, friend—and different environmental cues evoke different identities.

Cheryan called the phenomenon documented in her study “ambient belonging,” defined as individuals’ sense of fit with a physical environment, “along with a sense of fit with the people who are imagined to occupy that environment.”

Ambient belonging, she proposed, “can be ascertained rapidly, even from a cursory glance at a few objects.” In the research she has since produced, Cheryan has explored how ambient belonging can be enlarged and expanded—how a wider array of individuals can be induced to feel that crucial sense of “fit” in the environments in which they find themselves. The key, she says, is not to eliminate stereotypes but to diversify them—to convey the message that people from many different backgrounds can thrive in a given setting.

Taylorism - People as Machines and cold spaces

Frederick Winslow Taylor, the early-twentieth-century engineer who introduced “scientific management” to American corporations. Taylor specifically prohibited workers from bringing their personal effects into the factories he redesigned for maximum speed and minimum waste. Stripped of their individuality, he insisted, employees would function as perfectly efficient cogs in the industrial machine.

The burgeoning discipline of neuroarchitecture has begun to explore the way our brains respond to the built settings we encounter—finding, for example, that high-ceilinged places incline us toward more expansive, abstract thoughts.

Thinking with the Space of Ideas

Memory Champions

Brain wired for location memorization

The automatic place log maintained by our brains has been preserved by evolution because of its clear survival value: it was vitally important for our forebears to remember where they had found supplies of food or safe shelter, as well as where they had encountered predators and other dangers. The elemental importance of where such things were located means the mental tags attached to our place memories are often charged with emotion, positive or negative—making information about place even more memorable.

Capacity to lay ideas physically and interact with them

But true human genius lies in the way we are able to take facts and concepts out of our heads, using physical space to spread out that material, to structure it, and to see it anew.

On the most basic level, the author is using physical space to offload facts and ideas. He need not keep mentally aloft these pieces of information or the complex structure in which they are embedded; his posted outline holds them at the ready, granting him more mental resources to think about that same material. Keeping a thought in mind—while also doing things to and with that thought—is a cognitively taxing activity. We put part of this mental burden down when we delegate the representation of the information to physical space, something like jotting down a phone number instead of having to continually refresh its mental representation by repeating it under our breath.

Caro's Concept Map

Caro’s wall turns the mental “map” of his book into a stable external artifact.

A concept map is a visual representation of facts and ideas, and of the relationships among them. It can take the form of a detailed outline, as in Robert Caro’s case, but it is often more graphic and schematic in form.

Screen Real Estate

the availability of more screen pixels permits us to use more of our own “brain pixels” to understand and solve problems.

Large high-resolution displays allow users to deploy their “physical embodied resources,” says Ball, adding, “With small displays, much of the body’s built-in functionality is wasted.”

On small displays, information is contained within windows that are, of necessity, stacked on top of one another or moved around on the screen, interfering with our ability to relate to that information in terms of where it is located. By contrast, large displays, or multiple displays, offer enough space to lay out all the data in an arrangement that persists over time, allowing us to leverage our spatial memory as we navigate through that information.

Darwin advised those who would follow in his footsteps to “acquire the habit of writing very copious notes, not all for publication, but as a guide for himself.” The naturalist must take “precautions to attain accuracy,” he continued, “for the imagination is apt to run riot when dealing with masses of vast dimensions and with time during almost infinity.”

When thought overwhelms the mind, the mind

the very act of noticing and selecting points of interest to put down on paper initiates a more profound level of mental processing. 2023-07-03 21:58:22

Representations in the mind and representations on the page may seem roughly equivalent, when in fact they differ significantly in terms of what psychologists call their “affordances”—that is, what we’re able to do with them. External representations, for example, are more definite than internal ones. Picture a tiger, suggests philosopher Daniel Dennett in a classic thought experiment; imagine in detail its eyes, its nose, its paws, its tail. Following a few moments of conjuring, we may feel we’ve summoned up a fairly complete image. Now, says Dennett, answer this question: How many stripes does the tiger have? Suddenly the mental picture that had seemed so solid becomes maddeningly slippery. If we had drawn the tiger on paper, of course, counting its stripes would be a straightforward task. 2023-07-03 21:58:52

the “detachment gain”: the cognitive benefit we receive from putting a bit of distance between ourselves and the content of our minds. When we do so, we can see more clearly what that content is made of—how many stripes are on the tiger, so to speak. This measure of space also allows us to activate our powers of recognition. We leverage these powers whenever we write down two or more ways to spell a word, seeking the one that “looks right.” The curious thing about this common practice is that we do tend to know immediately which spelling appears correct—indicating that this is knowledge we already possess but can’t access until it is externalized. 2023-07-03 21:59:27

Architects, artists, and designers often speak of a “conversation” carried on between eye and hand; Goldschmidt makes the two-way nature of this conversation clear when she refers to “the backtalk of self-generated sketches.” 2023-07-03 22:00:35

thinking with your brain alone—like a computer does—is not equivalent to thinking with your brain, your eyes, and your hands.” 2023-07-03 22:03:07

Part III: Thinking with Our Relationships

Thinking with Experts

Collins and his coauthors identified four features of apprenticeship that could be adapted to the demands of knowledge work: modeling, or demonstrating the task while explaining it aloud; scaffolding, or structuring an opportunity for the learner to try the task herself; fading, or gradually withdrawing guidance as the learner becomes more proficient; and coaching, or helping the learner through difficulties along the way.

over the world, in every sector and specialty, education and work are less and less about executing concrete tasks and more and more about engaging in internal thought processes.

1st Advantage of Imitation

By copying others, imitators allow other individuals to act as filters, efficiently sorting through available options.

2nd Advantage of Imitation

Imitators can draw from a wide variety of solutions instead of being tied to just one.

They can choose precisely the strategy that is most effective in the current moment, making quick adjustments to changing conditions.

Zara’s adroit use of imitation has helped make Inditex the largest fashion apparel retailer in the world.

3rd Advantage of Imitation

Copiers can evade mistakes by steering clear of the errors made by others who went before them, while innovators have no such guide to potential pitfalls.

Companies that capitalize on others’ innovations have “a minimal failure rate” and “an average market share almost three times that of market pioneers,” they found. In this category they include Timex, Gillette, and Ford, firms that are often recalled—wrongly—as being first in their field.

4th Advantage of Imitation

Imitators are able to avoid being swayed by deception or secrecy: by working directly off of what others do, copiers get access to the best strategies in others’ repertoires.

Pape also became aware that aviation experts had devised a solution to the problem of pilot interruption: the “sterile cockpit rule.” Instituted by the Federal Aviation Administration in 1981, the rule forbids pilots from engaging in conversation unrelated to the immediate business of flying when the plane is below ten thousand feet.

In addition to the sterile cockpit concept Pape adapted, health care professionals have also borrowed from pilots the onboard “checklist”—a standardized rundown of tasks to be.

The medical field has also adopted the “peer-to-peer assessment technique,” a common practice in the nuclear power industry. A delegation from one hospital visits another hospital in order to conduct a “structured, confidential, and non-punitive review” of the host institution’s safety and quality efforts. Without the threat of sanctions carried by regulators, these peer reviews can surface problems and suggest fixes, making the technique itself a vehicle for constructive copying among organizations.

There is sense behind this seemingly irrational behavior. Humans’ tendency to “overimitate”—to reproduce even the gratuitous elements of another’s behavior—may operate on a copy now, understand later basis. After all, there might be good reasons for such steps that the novice does not yet grasp, especially since so many human tools and practices are “cognitively opaque”: not self-explanatory on their face.

Reenacting the experience of being a novice need not be so literal; experts can generate empathy for the beginner through acts of the imagination, changing the way they present information accordingly. An example: experts habitually engage in “chunking,” or compressing several tasks into one mental unit. This frees up space in the expert’s working memory, but it often baffles the novice, for whom each step is new and still imperfectly understood. A math teacher may speed through an explanation of long division, not remembering or recognizing that the procedures that now seem so obvious were once utterly inscrutable. Math education expert John Mighton has a suggestion: break it down into steps, then break it down again—into micro-steps, if necessary.

Third difference between experts and novices lies in the way they categorize what they see: novices sort the entities they encounter according to their superficial features, while experts classify them according to their deep function 2023-07-08 00:02:33

Experts have another edge over novices: they know what to attend to and what to ignore. Presented with a professionally relevant scenario, experts will immediately home in on its most salient aspects, while beginners waste their time focusing on unimportant features. 2023-07-08 00:02:59

These strategies—breaking down agglomerated steps, exaggerating salient features, supplying categories based on function—help pry open the black box of experts’ automatized knowledge and skill. 2023-07-08 00:03:40

Thinking with Peers

Our brains evolved to think with people: to teach them, to argue with them, to exchange stories with them. Human thought is exquisitely sensitive to context, and one of the most powerful contexts of all is the presence of other people. 2023-07-08 00:07:29

To offer just one example: the brain stores social information differently than it stores information that is non-social. Social memories are encoded in a distinct region of the brain. What’s more, we remember social information more accurately, a phenomenon that psychologists call the “social encoding advantage.” 2023-07-08 00:08:08

social interactions with other people alter our physiological state in ways that enhance learning, generating a state of energized alertness that sharpens attention and reinforces memory. Students who are studying on their own experience no such boost in physiological arousal, and so easily become bored or distracted; they may turn on music or open up Instagram to give themselves a dose of the human emotion and social stimulation they’re missing. 2023-07-09 00:05:45

Such outcomes may be due, in part, to the experience of what psychologists call “productive agency”: the sense that one’s own actions are affecting another person in a beneficial way. 2023-07-09 00:07:21

It is “a general rule of teaching,” he has written, “that if an instructor does not create an intellectual conflict within the first few minutes of class, students won’t engage with the lesson.” 2023-07-09 00:13:23

“constructive controversy,” or the open-minded exploration of diverging ideas and beliefs. In his studies, Johnson has found that students who are drawn into an intellectual dispute read more library books, review more classroom materials, and seek out more information from others in the know. Conflict creates uncertainty—who’s wrong? who’s right?—an ambiguity that we feel compelled to resolve by acquiring more facts. 2023-07-09 00:13:40

Intellectual clashes can also generate what psychologists call “the accountability effect.” Just as students prepare more assiduously when they know they’ll be teaching the material to others, people who know they’ll be called upon to defend their views marshal stronger points, and support them with more and better evidence, than people who anticipate merely presenting their opinions in writing. 2023-07-09 00:14:01

We use argument to its full advantage when we make the best case for our own position while granting the points lodged against it; when we energetically critique our partner’s position while remaining open to its potential virtues. According to Robert Sutton, the Stanford business school professor, we should endeavor to offer “strong opinions, weakly held”; put another way, he says, “People should fight as if they are right, and listen as if they are wrong.” 2023-07-09 00:15:03

Thinking with Groups

In business and education, in public and private life, we emphasize individual competition over joint cooperation. We resist what we consider conformity (at least in its overt, organized form), and we look with suspicion on what we call “groupthink.” 2023-07-09 00:16:43

The benefits of this activity—practiced by everyone from the youngest schoolchildren to top executives at Sony and Toyota—may go well beyond fitness and flexibility for those who take part. A substantial body of research shows that behavioral synchrony—coordinating our actions, including our physical movements, so that they are like the actions of others—primes us for what we might call cognitive synchrony: multiple people thinking together efficiently and effectively. 2023-07-09 00:18:13

By one year of age, a baby will reliably look in the direction of an adult’s gaze, even absent the turning of the adult’s head. Such gaze-following is made easier by the fact that people have visible whites of the eyes. Humans are the only primates so outfitted, an exceptional status that has led scientists to propose the “cooperative eye hypothesis”—the theory that our eyes evolved to support cooperative social interactions. “Our eyes see, but they are also meant to be seen,” notes science writer Ker Than. 2023-07-09 00:21:07

Psychologists have found that groups differ widely on what they call “entitativity”—or, in a catchier formulation, their “groupiness.” Some portion of the time and effort we devote to cultivating our individual talents could more productively be spent on forming teams that are genuinely groupy.

In order to foster a sense of groupiness, there are a few deliberate steps we can take. First, people who need to think together should learn together—in person, at the same time. 2023-07-09 00:22:06

third principle for generating groupiness would hold that people who need to think together should feel together—in person, at the same time. Laboratory research, as well as research conducted with survivors of battlefield conflicts and natural disasters, has found that emotionally distressing or physically painful events can act as a kind of “social glue” that bonds the people who experienced them together. But the emotions that unite a group need not be so harrowing. Studies have also determined that simply asking members to candidly share their thoughts and feelings with one another leads to improvements in group cohesion and performance. 2023-07-09 00:23:43

“When people stop and reflect, and then say, one at a time, how each of them are really feeling, it opens up a deeper level of dialogue.” 2023-07-09 00:24:04

“almost everything that human beings do today, in terms of generation of value, is no longer done by individuals. It’s done by teams.” 2023-07-09 00:28:26

One solution, says Sunstein, is for leaders to silence themselves; the manager or administrator who adopts an “inquisitive and self-silencing” stance, he maintains, has the best chance of hearing more than his own views reflected back to him. 2023-07-09 00:30:08

researchers recommend that we implement a specific sequence of actions in response to our teammates’ contributions: we should acknowledge, repeat, rephrase, and elaborate on what other group members say. Studies show that engaging in this kind of communication elicits more complete and comprehensive information. It re-exposes the entire group to the information that was shared initially, improving group members’ understanding of and memory for that information. And it increases the accuracy of the information that is shared, a process that psychologists call “error pruning.” Although it may seem cumbersome or redundant, research suggests that this kind of enhanced communication is part of what makes expert teamwork so effective. 2023-07-09 00:30:58

There’s a third way in which group thinking diverges from individual thinking: when engaged in the latter, we of course have access to the full depth of our own knowledge and skill. That’s not the case when we’re thinking collectively—and that’s a good thing. One of the great advantages of the group mind is its capacity to bring together many and varied areas of proficiency, ultimately encompassing far more expertise than could ever be held in a single mind. 2023-07-09 00:32:42

The process by which we leverage an awareness of the knowledge other people possess is called “transactive memory.” 2023-07-09 00:32:58

Research shows that groups perform best when each member is clearly in charge of maintaining a particular body of expertise—when each topic has its designated “knowledge champion,” as it were. Studies further suggest that it can be useful to appoint a meta-knowledge champion: an individual who is responsible for keeping track of what others in the group know and making sure that group members’ mental “directory” of who knows what stays up to date. 2023-07-09 00:34:03

They called their procedure the “jigsaw classroom.”

This is how it worked: Students were divided into groups of five or six. When a class began a new unit—say, on the life of Eleanor Roosevelt—each student in the group was assigned one section of the material: Roosevelt’s childhood and young adulthood, or her role as first lady, or her work on behalf of causes such as civil rights and world peace. The students’ task was to master their own section, then rejoin the group and report to the others on what they had learned. “Each student has possession of a unique and vital part of the information, which, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, must be put together before anyone can learn the whole picture,” 2023-07-09 00:35:07

Conclusion

The capacity to think intelligently emerges from the skillful orchestration of these internal and external elements. And indeed, studies have shown that such mental extensions can help us think more effectively when confronted with a challenge like stereotype threat. Using “cognitive reappraisal” to reinterpret bodily signals, as we learned to do in chapter 1, can head off the performance-suppressing effects of anxiety. Adding “cues of belonging” to the physical environment, of the kind we explored in chapter 5, can generate a sense of psychological ease that’s conducive to intelligent thought. And carefully structuring the expert feedback offered to a “cognitive apprentice,” as we learned about in chapter 7, can instill the confidence necessary to overcome self-doubt. 2023-07-09 00:37:17

Mental Extensions

In this book we’ve looked intently at one extension at a time: interoceptive signals, movements, and gestures; natural spaces, built spaces, and the “space of ideas”; experts, peers, and groups.

Extensions are most powerful when they are employed in combination, incorporated into mental routines that draw on the full range of extra-neural resources we have at hand.

1st Principle

Whenever possible, we should offload information, externalize it, move it out of our heads and into the world. Throughout this book we’ve encountered many examples of offloading and have become familiar with its manifold benefits. It relieves us of the burden of keeping a host of details “in mind,” thereby freeing up mental resources for more demanding tasks, like problem solving and idea generation. It also produces for us the “detachment gain,” whereby we can inspect with our senses, and often perceive anew, an image or idea that once existed only in the imagination.

2nd Principle

Whenever possible, we should endeavor to transform information into an artifact, to make data into something real—and then proceed to interact with it, labeling it, mapping it, feeling it, tweaking it, showing it to others. Humans evolved to handle the concrete, not to contemplate the abstract.

3rd Principle

Whenever possible, we should seek to productively alter our own state when engaging in mental labor.

4th Principle

Whenever possible, we should offload information, externalize it, move it out of our heads and into the world.

5th Principle

Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-spatialize the information we think about.

4th Principle

Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-embody the information we think about. The pursuit of knowledge has frequently sought to disengage.

6th Principle

Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-socialize the information we think about.

As Andy Clark has pointed out, when computer scientists develop artificial intelligence systems, they don’t design machines that compute for a while, print out the results, inspect what they have produced, add some marks in the margin, circulate copies among colleagues, and then start the process again. That’s not how computers work—but it is how we work; we are “intrinsically loopy creatures,” as Clark likes to say.

7th Principle

whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by generating cognitive loops.

8th Principle

Whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by creating cognitively congenial situations.

9th Principle

whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by embedding extensions in our everyday environments.

📋 Table of Contents

Title Page

Contents

Dedication

Copyright

Prologue

Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain

Part I: Thinking with Our Bodies

Thinking with Sensations

Thinking with Movement

Thinking with Gesture

Part II: Thinking with Our Surroundings

Thinking with Natural Spaces

Thinking with Built Spaces

Thinking with the Space of Ideas

Part III: Thinking with Our Relationships

Thinking with Experts

Thinking with Peers

Thinking with Groups

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Author

ℹ️ About

🥩 Raw Notes

| koreader-sync.data.chapter128 | koreader-sync.data.highlight | koreader-sync.data.datetime |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Thinking outside the brain means skillfully engaging entities external to our heads—the feelings and movements of our bodies, the physical spaces in which we learn and work, and the minds of the other people around us—drawing them into our own mental processes. By reaching beyond the brain to recruit these “extra-neural” resources, we are able to focus more intently, comprehend more deeply, and create more imaginatively—to entertain ideas that would be literally unthinkable by the brain alone. | 2023-06-13 20:40:50 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | The human brain is limited in its ability to pay attention, limited in its capacity to remember, limited in its facility with abstract concepts, and limited in its power to persist at a challenging task. | 2023-06-19 21:23:48 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Our approach constitutes an instance of (as the poet William Butler Yeats put it in another context) “the will trying to do the work of the imagination.” The smart move is not to lean ever harder on the brain but to learn to reach beyond it. | 2023-06-19 21:25:41 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Beginning in elementary school, we are taught to sit still, work quietly, think hard—a model for mental activity that will prevail during all the years that follow, through high school and college and into the workplace. The skills we develop and the techniques we are taught are those that involve using our heads: committing information to memory, engaging in internal reasoning and deliberation, endeavoring to self-discipline and self-motivate. | |

| Meanwhile, there is no corresponding cultivation of our ability to think outside the brain—no instruction, for instance, in how to tune in to the body’s internal signals, sensations that can profitably guide our choices and decisions. We’re not trained to use bodily movements and gestures to understand highly conceptual subjects like science and mathematics, or to come up with novel and original ideas. Schools don’t teach students how to restore their depleted attention with exposure to nature and the outdoors, or how to arrange their study spaces so that they extend intelligent thought. Teachers and managers don’t demonstrate how abstract ideas can be turned into physical objects that can be manipulated and transformed in order to achieve insights and solve problems. Employees aren’t shown how the social practices of imitation and vicarious learning can shortcut the process of acquiring expertise. Classroom groups and workplace teams aren’t coached in scientifically validated methods of increasing the collective intelligence of their members. Our ability to think outside the brain has been left almost entirely uneducated and undeveloped. | 2023-06-19 21:27:45 | |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | the brain is not actually a muscle but rather an organ made up of specialized cells known as neurons.) | 2023-06-19 21:29:56 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Our brains, it might be said, are like magpies, fashioning their finished products from the materials around them, weaving the bits and pieces they find into their trains of thought. Set beside the brain-as-computer and brain-as-muscle metaphors, it’s apparent that the brain as magpie is a very different kind of analogy, with very different implications for how mental processes operate. For one thing: thought happens not only inside the skull but out in the world, too; it’s an act of continuous assembly and reassembly that draws on resources external to the brain. For another: the kinds of materials available to “think with” affect the nature and quality of the thought that can be produced. And last: the capacity to think well—that is, to be intelligent—is not a fixed property of the individual but rather a shifting state that is dependent on access to extra-neural resources and the knowledge of how to use them. | 2023-06-20 00:12:26 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | David Geary, a professor of psychology at the University of Missouri, makes a useful distinction between “biologically primary” and “biologically secondary” abilities. | 2023-06-20 00:14:22 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Two years earlier, Clark and his colleague David Chalmers had coauthored an article that named and described just this phenomenon. Their paper, titled “The Extended Mind,” began by posing a question that would seem to have an obvious answer. “Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin?” it asked. Clark and Chalmers went on to offer an unconventional response. The mind does not stop at the standard “demarcations of skin and skull,” they argued. Rather, it is more accurately viewed as “an extended system, a coupling of biological organism and external resources.” | 2023-06-24 22:49:37 |

| Introduction: Thinking Outside the Brain | Traditional notions of what makes an expert are highly brainbound, focused on internal, individual effort (think of the late psychologist Anders Ericsson’s famous finding that mastery in any field requires “10,000 hours” of practice). The literature on the extended mind suggests a different view: experts are those who have learned how best to marshal and apply extra-neural resources to the task before them. | 2023-06-24 22:52:34 |

| Thinking with Sensations | the size and activity level of the brain’s interoceptive hub, the insula, vary among individuals and are correlated with their awareness of interoceptive sensations. | 2023-06-24 22:58:31 |

| Thinking with Sensations | What we do know is that interoceptive awareness can be deliberately cultivated. A series of simple exercises can put us in touch with the messages emanating from within, giving us access to knowledge that we already possess but that is ordinarily excluded from consciousness—knowledge about ourselves, about other people, and about the worlds through which we move. | 2023-06-24 22:59:05 |

| Thinking with Sensations | “Nonconscious information acquisition,” as Lewicki calls it, along with the ensuing application of such information, is happening in our lives all the time. As we navigate a new situation, we’re scrolling through our mental archive of stored patterns from the past, checking for ones that apply to our current circumstances. We’re not aware that these searches are under way; as Lewicki observes, “The human cognitive system is not equipped to handle such tasks on the consciously controlled level.” He adds, “Our conscious thinking needs to rely on notes and flowcharts and lists of ‘if-then’ statements—or on computers—to do the same job which our non-consciously operating processing algorithms can do without external help, and instantly.” | 2023-06-24 23:00:09 |

| Thinking with Sensations | when a potentially relevant pattern is detected, it’s our interoceptive faculty that tips us off: with a shiver or a sigh, a quickening of the breath or a tensing of the muscles. The body is rung like a bell to alert us to this useful and otherwise inaccessible information. | 2023-06-24 23:00:26 |

| Thinking with Sensations | people who are more aware of their bodily sensations are better able to make use of their non-conscious knowledge. Mindfulness meditation is one way of enhancing such awareness. | 2023-06-25 16:43:59 |

| Thinking with Sensations | “People find the body scan beneficial because it reconnects their conscious mind to the feeling states of their body,” says Kabat-Zinn. “By practicing regularly, people usually feel more in touch with sensations in parts of their body they had never felt or thought much about before.” | 2023-06-25 16:44:53 |

| Thinking with Sensations | The body scan trains us to observe such sensations with interest and equanimity. But tuning in to these feelings is only a first step. The next step is to name them. Attaching a label to our interoceptive sensations allows us to begin to regulate them; without such attentive self-regulation, we may find our feelings overwhelming, or we may misinterpret their source. | 2023-06-25 16:45:57 |

| Thinking with Sensations | The practice of affect labeling, like the body scan, is a kind of mental training intended to get us into the habit of noting and naming the sensations that arise in our bodies. | 2023-06-25 16:47:23 |

| Thinking with Sensations | Attempts to reduce biases by learning about biases and engaging in self-monitoring rapidly come up against human cognitive limits.” | 2023-06-25 16:53:20 |

| Thinking with Sensations | The body and its interoceptive capacities can also play another role: as the coach who pushes us to pursue our goals, to persevere in the face of adversity, to return from setbacks with renewed energy. In a word, an awareness of our interoception can help us become more resilient. | 2023-06-25 16:57:09 |

| Thinking with Sensations | The ability to allocate our internal resources effectively in tackling mental challenges is a capacity researchers call “cognitive resilience.” | 2023-06-25 17:02:00 |

| Thinking with Sensations | Mindfulness-based Mind Fitness Training, designed to bolster the cognitive resilience of service members facing high-stress situations. MMFT, as it is known, places an emphasis on recognizing and regulating the body’s internal signals. In | 2023-06-25 17:03:55 |

| Thinking with Sensations | the most cognitively resilient soldiers pay close attention to their bodily sensations at the early stage of a challenge, when signs of stress are just beginning to accumulate | 2023-06-25 17:04:36 |

| Thinking with Sensations | Stanley also demonstrates for her students a technique she calls “shuttling”—moving one’s focus back and forth between what is transpiring internally and what is going on outside the body. Such shifts are useful in ensuring that we are neither too caught up in external events nor too overwhelmed by our internal feelings, but instead occupy a place of balance that incorporates input from both realms. This alternation of attention can be practiced at relaxed moments until it becomes second nature: a continuously repeated act of checking in that provides a periodic infusion of interoceptive information. The point is to keep in close contact with our internal reality at all times—to train ourselves “to pay attention and notice what’s happening while it’s happening,” as Stanley puts | 2023-06-25 17:05:53 |

| Thinking with Sensations | the thing we call “emotion” (and experience as a unified whole) is actually constructed from more elemental parts; these parts include the signals generated by the body’s interoceptive system, as well as the beliefs of our families and cultures regarding how these signals are to be interpreted | 2023-06-25 17:08:51 |

| Thinking with Sensations | we can choose to reappraise debilitating “stress” as productive “coping.” A 2010 study carried out with Boston-area undergraduates looked at what happens when people facing a stressful experience are informed about the positive effects of stress on our thinking—that is, the way it can make us more alert and more motivated. | 2023-06-25 17:14:21 |

| Thinking with Sensations | When employing the reappraisal approach, the students answered more of the math questions correctly, and the scans showed why: brain areas involved in executing arithmetic were more active under the reappraisal condition. The increased activity in these areas suggests that the act of reappraisal allowed students to redirect the mental resources that previously were consumed by anxiety, applying them to the math problems instead. | 2023-06-25 17:15:01 |

| Thinking with Sensations | When interacting with other people, we subtly and unconsciously mimic their facial expressions, gestures, posture, and vocal pitch. Then, via the interoception of our own bodies’ signals, we perceive what the other person is feeling because we feel it in ourselves. We bring other people’s feelings onboard, and the body is the bridge. | 2023-06-25 17:16:20 |

| Thinking with Movement | Scientists have long known that overall physical fitness supports cognitive function; people who have fitter bodies generally have keener minds. | 2023-06-25 17:36:28 |

| Thinking with Movement | One study found that people who were directed to doodle while carrying out a boring listening task remembered 29 percent more information than people who did not doodle, likely because the latter group had let their attention slip away entirely. | 2023-06-25 17:44:15 |

| Thinking with Movement | we have it within our power to induce in ourselves a state that is ideal for learning, creating, and engaging in other kinds of complex cognition: by exercising briskly just before we do so | 2023-06-25 17:46:58 |

| Thinking with Movement | Another misguided idea about breaks: they should be used to rest the body, so as to fortify us for the next round of mental labor. As we’ve seen, it’s through exerting the body that our brains become ready for the kind of knowledge work so many of us do today. The best preparation for such (metaphorical) acts as wrestling with ideas or running through possibilities is to work up an (actual) sweat. Instead of languidly sipping a latte before tackling a difficult project, we should be taking an energetic walk around the block. | 2023-06-25 17:48:35 |

| Thinking with Movement | On his walks along the coastal California hills, Daniel Kahneman noticed that moving very fast “brings about a sharp deterioration in my ability to think coherently.” This observation, too, is supported by research: scientists draw what they call an “inverted U-shaped curve” to describe the relationship between exercise intensity and cognitive function, with the greatest benefits for thinking detected in the moderate-intensity middle part of the hump. | 2023-06-25 17:49:54 |

| Thinking with Movement | I run in order to acquire a void.” | |

| Scientists have a term for the “void” Murakami describes: “transient hypofrontality.” Hypo means low or diminished, and frontality refers to the frontal region of the brain—the part that plans, analyzes, and critiques, and that usually maintains firm control over our thoughts and behavior. | 2023-06-25 17:52:01 | |

| Thinking with Movement | When all of our resources are devoted to managing the demands of intense physical activity, however, the influence of the prefrontal cortex is temporarily reduced. In this loose hypofrontal mode, ideas and impressions mingle more freely; unusual and unexpected thoughts arise. | 2023-06-25 17:52:14 |

| Thinking with Movement | Linking movement to the material to be recalled creates a richer and therefore more indelible “memory trace” in the brain. In addition, movements engage a process called procedural memory (memory of how to do something, such as how to ride a bike) that is distinct from declarative memory (memory of informational content, such as the text of a speech). When we connect movement with information, we activate both types of memory, and our recall is more accurate as a result—a phenomenon that researchers call the “enactment effect.” | 2023-06-25 17:54:12 |

| Thinking with Movement | To take one example: by moving our bodies, we activate a deeply ingrained and mostly unconscious metaphor connecting dynamic motion with dynamic thinking. Call to mind the words we use when we can’t seem to muster an original idea—we’re “stuck,” “in a rut”—and those we reach for when we feel visited by the muse. Then we’re “on a roll,” our thoughts are “flowing.” Research has demonstrated that people can be placed in a creative state of mind by physically acting out creativity-related figures of speech—like “thinking outside the box.” | 2023-06-25 22:33:27 |

| Thinking with Movement | “Walking opens up the free flow of ideas,” the authors conclude. Studies by other researchers have even suggested that following a meandering, free-form route—as opposed to a fixed and rigid one—may further enhance creative thought processes. | 2023-06-25 22:35:11 |

| Thinking with Movement | That same year, Thoreau expanded on the theme in his journal. “How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!” he exclaimed. “Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.” | 2023-06-25 22:36:47 |

| Thinking with Gesture | psychologist Barbara Tversky has likened gesturing to a “virtual diagram” we draw in the air, one we can use to stabilize and advance our emerging understanding. As our comprehension deepens, our language becomes more precise and our movements become more defined. Gestures are less frequent, and more coordinated in meaning and timing with the words we say. Our hand motions are now more oriented toward communicating with others and less about scaffolding our own thinking. | 2023-06-26 23:14:16 |

| Thinking with Gesture | Research shows that moving our hands advances our understanding of abstract or complex concepts, reduces our cognitive load, and improves our memory. Making gestures also helps us get our message across to others with more persuasive force. | 2023-06-26 23:21:00 |

| Thinking with Gesture | That’s because gesturing while speaking involves sinking multiple mental “hooks” into the material to be remembered—hooks that enable us to reel in that piece of information when it is needed later on. There is the auditory hook: we hear ourselves saying the words aloud. There is the visual hook: we see ourselves making the relevant gesture. And there is the “proprioceptive” hook; this comes from feeling our hands make the gesture. (Proprioception is the sense that allows us to know where our body parts are positioned in space.) Surprisingly, this proprioceptive cue may be the most powerful of the three: research shows that making gestures enhances our ability to think even when our gesturing hands are hidden from our view. | 2023-06-28 19:25:57 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | Drivers who travel along tree-lined roads, for example, recover more quickly from stressful experiences, and handle emerging stresses with more calm, than do people who drive along roads crowded with billboards, buildings, and parking lots. | 2023-06-28 22:10:28 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | The sights and sounds of nature help us rebound from stress; they can also help us out of a mental rut. “Rumination” is psychologists’ term for the way we may fruitlessly visit and revisit the same negative thoughts. On our own, we can find it difficult to pull ourselves out of this cycle—but exposure to nature can extend our ability to adopt more productive thought patterns. | 2023-06-28 22:11:22 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | There are two kinds of attention, wrote James in his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology: “voluntary” and “passive.” Voluntary attention takes effort; we must continually direct and redirect our focus as we encounter an onslaught of stimuli or concentrate hard on a task. Navigating an urban environment—with its hard surfaces, sudden movements, and loud, sharp noises—requires voluntary attention. Passive attention, by contrast, is effortless: diffuse and unfocused, it floats from object to object, topic to topic. This is the kind of attention evoked by nature, with its murmuring sounds and fluid motions; psychologists working in the tradition of James call this state of mind “soft fascination.” | 2023-06-28 22:15:09 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | it’s not the speed of the journey, it’s what you see along the way. | 2023-06-28 22:18:49 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | within twenty to sixty seconds of exposure to nature, our heart rate slows, our blood pressure drops, our breathing becomes more regular, and our brain activity becomes more relaxed. Even our eye movements change: We gaze longer at natural scenes than at built ones, shifting our focus less frequently. We blink less often when viewing nature than when looking at urban settings, indicating that nature imposes a less burdensome cognitive load. | 2023-06-28 22:28:56 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | Even a brief glance out the window can make a difference in our mental capacity. | 2023-06-28 22:45:52 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | We can seek out such “microrestorative opportunities” throughout the day, replenishing our mental resources with each glance out the window. | 2023-06-28 22:45:59 |

| Thinking with Natural Spaces | spending time in nature can promote innovative thinking. Scientists theorize that the “soft fascination” evoked by natural scenes engages what’s known as the brain’s “default mode network.” When this network is activated, we enter a loose associative state in which we’re not focused on any one particular task but are receptive to unexpected connections and insights. In nature, few decisions and choices are demanded of us, granting our minds the freedom to follow our thoughts wherever they lead. At the same time, nature is pleasantly diverting, in a fashion that lifts our mood without occupying all our mental powers; such positive emotion in turn leads us to think more expansively and open-mindedly. | 2023-06-28 22:58:00 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | “The wall was designed to protect us from the cognitive load of having to keep track of the activities of strangers,” observes Colin Ellard, an environmental psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Waterloo in Canada. “This became increasingly important as we moved from tiny agrarian settlements to larger villages and, eventually, to cities—where it was too difficult to keep track of who was doing what to whom.” | 2023-07-02 00:13:59 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | What about wearing headphones? That takes the problem and puts it directly into our ears. Like overheard speech, music with lyrics competes for mental resources with activities that also involve language, such as reading and writing. | 2023-07-02 11:53:34 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Our attention is pulled especially powerfully to the gaze of other people; we are uncannily sensitive to the feeling of being observed. Once we spot others’ eyes on us, the processing of eye contact takes precedence over whatever else our brains were working on. | 2023-07-02 11:55:25 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | All this visual monitoring and processing uses up considerable mental resources, leaving that much less brainpower for our work. We know this because of how much better we think when we close our eyes. | 2023-07-02 11:55:42 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Of course, we can hardly go about our work or our learning with our eyes closed. We have to rely on elements of physical space to save us from our own propensity for distraction—to impose the “sensory reduction” that supports optimal attention, memory, and cognition. “Good fences make good neighbors,” wrote poet Robert Frost; likewise, good walls make good collaborators. | 2023-07-02 11:56:19 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Other studies have found that as workspaces become more open, trust and cooperativeness among co-workers declines. The open-plan office seems to discourage exactly the kind of behavior it was intended to promote. | 2023-07-02 11:59:28 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | when people occupy spaces that they consider their own, they experience themselves as more confident and capable. They are more efficient and productive. They are more focused and less distractible. And they advance their own interests more forcefully and effectively. A study by psychologists | 2023-07-02 12:00:10 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | the importance of solitude is also structured into the timetable through the commitment to twice-daily private prayer, as well as the summum silentium (complete silence, sometimes referred to as ‘the great silence’) at the end of the day,” | 2023-07-02 14:14:38 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | The ancient arrangement of space in a monastery bears some resemblance to today’s “activity-based workspaces,” which nod to the human need for both social interaction and undisturbed solitude by providing dedicated areas for each: a café-style meeting place, a soundproof study carrel with a door. | 2023-07-02 14:17:42 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Research shows that in the presence of cues of identity and cues of affiliation, people perform better: they’re more motivated and more productive. | 2023-07-02 14:18:56 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | As the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has written, we keep certain objects in view because “they tell us things about ourselves that we need to hear in order to keep our selves from falling apart.” | 2023-07-02 14:22:53 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Moreover, we need to have close at hand those prompts that highlight particular facets of our identity. Each of us has not one identity but many —worker, student, spouse, parent, friend—and different environmental cues evoke different identities. | 2023-07-02 14:23:09 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Frederick Winslow Taylor, the early-twentieth-century engineer who introduced “scientific management” to American corporations. Taylor specifically prohibited workers from bringing their personal effects into the factories he redesigned for maximum speed and minimum waste. Stripped of their individuality, he insisted, employees would function as perfectly efficient cogs in the industrial machine. | 2023-07-02 14:25:25 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | Cheryan called the phenomenon documented in her study “ambient belonging,” defined as individuals’ sense of fit with a physical environment, “along with a sense of fit with the people who are imagined to occupy that environment.” Ambient belonging, she proposed, “can be ascertained rapidly, even from a cursory glance at a few objects.” In the research she has since produced, Cheryan has explored how ambient belonging can be enlarged and expanded—how a wider array of individuals can be induced to feel that crucial sense of “fit” in the environments in which they find themselves. The key, she says, is not to eliminate stereotypes but to diversify them—to convey the message that people from many different backgrounds can thrive in a given setting. | 2023-07-02 14:30:05 |

| Thinking with Built Spaces | The burgeoning discipline of neuroarchitecture has begun to explore the way our brains respond to the built settings we encounter—finding, for example, that high-ceilinged places incline us toward more expansive, abstract thoughts. | 2023-07-02 14:47:10 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | “method of loci”: a mental strategy that draws on the powerful connection to place that all humans share. | |

| The method of loci is a venerable technique, invented by the ancient Greeks and used by educators and orators over many centuries. | 2023-07-02 14:52:27 | |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | difference between “superior memorizers” and ordinary people, Maguire determined, lay in the parts of the brain that became active when the two groups engaged in the act of recall; in the memory champions’ brains, regions associated with spatial memory and navigation were highly engaged, while in ordinary people these areas were much less active. | 2023-07-02 14:58:32 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | The automatic place log maintained by our brains has been preserved by evolution because of its clear survival value: it was vitally important for our forebears to remember where they had found supplies of food or safe shelter, as well as where they had encountered predators and other dangers. The elemental importance of where such things were located means the mental tags attached to our place memories are often charged with emotion, positive or negative—making information about place even more memorable. | 2023-07-02 15:04:13 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | But true human genius lies in the way we are able to take facts and concepts out of our heads, using physical space to spread out that material, to structure it, and to see it anew. | 2023-07-02 15:11:11 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | On the most basic level, the author is using physical space to offload facts and ideas. He need not keep mentally aloft these pieces of information or the complex structure in which they are embedded; his posted outline holds them at the ready, granting him more mental resources to think about that same material. Keeping a thought in mind—while also doing things to and with that thought—is a cognitively taxing activity. We put part of this mental burden down when we delegate the representation of the information to physical space, something like jotting down a phone number instead of having to continually refresh its mental representation by repeating it under our breath. | |

| Caro’s wall turns the mental “map” of his book into a stable external artifact. | 2023-07-02 15:15:39 | |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | A concept map is a visual representation of facts and ideas, and of the relationships among them. It can take the form of a detailed outline, as in Robert Caro’s case, but it is often more graphic and schematic in form. | 2023-07-02 15:16:34 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | the availability of more screen pixels permits us to use more of our own “brain pixels” to understand and solve problems. | 2023-07-03 21:54:50 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | Large high-resolution displays allow users to deploy their “physical embodied resources,” says Ball, adding, “With small displays, much of the body’s built-in functionality is wasted.” | 2023-07-03 21:55:17 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | on small displays, information is contained within windows that are, of necessity, stacked on top of one another or moved around on the screen, interfering with our ability to relate to that information in terms of where it is located. By contrast, large displays, or multiple displays, offer enough space to lay out all the data in an arrangement that persists over time, allowing us to leverage our spatial memory as we navigate through that information. | 2023-07-03 21:55:52 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | Darwin advised those who would follow in his footsteps to “acquire the habit of writing very copious notes, not all for publication, but as a guide for himself.” The naturalist must take “precautions to attain accuracy,” he continued, “for the imagination is apt to run riot when dealing with masses of vast dimensions and with time during almost infinity.” | |

| When thought overwhelms the mind, the mind | 2023-07-03 21:57:19 | |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | the very act of noticing and selecting points of interest to put down on paper initiates a more profound level of mental processing. | 2023-07-03 21:58:22 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | Representations in the mind and representations on the page may seem roughly equivalent, when in fact they differ significantly in terms of what psychologists call their “affordances”—that is, what we’re able to do with them. External representations, for example, are more definite than internal ones. Picture a tiger, suggests philosopher Daniel Dennett in a classic thought experiment; imagine in detail its eyes, its nose, its paws, its tail. Following a few moments of conjuring, we may feel we’ve summoned up a fairly complete image. Now, says Dennett, answer this question: How many stripes does the tiger have? Suddenly the mental picture that had seemed so solid becomes maddeningly slippery. If we had drawn the tiger on paper, of course, counting its stripes would be a straightforward task. | 2023-07-03 21:58:52 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | the “detachment gain”: the cognitive benefit we receive from putting a bit of distance between ourselves and the content of our minds. When we do so, we can see more clearly what that content is made of—how many stripes are on the tiger, so to speak. This measure of space also allows us to activate our powers of recognition. We leverage these powers whenever we write down two or more ways to spell a word, seeking the one that “looks right.” The curious thing about this common practice is that we do tend to know immediately which spelling appears correct—indicating that this is knowledge we already possess but can’t access until it is externalized. | 2023-07-03 21:59:27 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | Architects, artists, and designers often speak of a “conversation” carried on between eye and hand; Goldschmidt makes the two-way nature of this conversation clear when she refers to “the backtalk of self-generated sketches.” | 2023-07-03 22:00:35 |

| Thinking with the Space of Ideas | thinking with your brain alone—like a computer does—is not equivalent to thinking with your brain, your eyes, and your hands.” | 2023-07-03 22:03:07 |

| Thinking with Experts | Collins and his coauthors identified four features of apprenticeship that could be adapted to the demands of knowledge work: modeling, or demonstrating the task while explaining it aloud; scaffolding, or structuring an opportunity for the learner to try the task herself; fading, or gradually withdrawing guidance as the learner becomes more proficient; and coaching, or helping the learner through difficulties along the way. | 2023-07-04 00:43:03 |

| Thinking with Experts | over the world, in every sector and specialty, education and work are less and less about executing concrete tasks and more and more about engaging in internal thought processes | 2023-07-04 00:43:31 |

| Thinking with Experts | First on the list: by copying others, imitators allow other individuals to act as filters, efficiently sorting through available options. | 2023-07-04 00:50:34 |

| Thinking with Experts | Second: imitators can draw from a wide variety of solutions instead of being tied to just one. | 2023-07-04 00:50:50 |

| Thinking with Experts | They can choose precisely the strategy that is most effective in the current moment, making quick adjustments to changing conditions. | 2023-07-04 00:50:56 |

| Thinking with Experts | Zara’s adroit use of imitation has helped make Inditex the largest fashion apparel retailer in the world | 2023-07-04 00:51:28 |

| Thinking with Experts | The third advantage of imitation: copiers can evade mistakes by steering clear of the errors made by others who went before them, while innovators have no such guide to potential pitfalls. | 2023-07-04 00:51:39 |

| Thinking with Experts | Companies that capitalize on others’ innovations have “a minimal failure rate” and “an average market share almost three times that of market pioneers,” they found. In this category they include Timex, Gillette, and Ford, firms that are often recalled—wrongly—as being first in their field. | 2023-07-04 00:52:25 |

| Thinking with Experts | Fourth, imitators are able to avoid being swayed by deception or secrecy: by working directly off of what others do, copiers get access to the best strategies in others’ repertoires. | 2023-07-04 00:52:36 |

| Thinking with Experts | Pape also became aware that aviation experts had devised a solution to the problem of pilot interruption: the “sterile cockpit rule.” Instituted by the Federal Aviation Administration in 1981, the rule forbids pilots from engaging in conversation unrelated to the immediate business of flying when the plane is below ten thousand feet. | 2023-07-04 00:54:36 |

| Thinking with Experts | In addition to the sterile cockpit concept Pape adapted, health care professionals have also borrowed from pilots the onboard “checklist”—a standardized rundown of tasks to be | 2023-07-04 00:55:55 |

| Thinking with Experts | The medical field has also adopted the “peer-to-peer assessment technique,” a common practice in the nuclear power industry. A delegation from one hospital visits another hospital in order to conduct a “structured, confidential, and non-punitive review” of the host institution’s safety and quality efforts. Without the threat of sanctions carried by regulators, these peer reviews can surface problems and suggest fixes, making the technique itself a vehicle for constructive copying among organizations. | 2023-07-04 00:56:13 |

| Thinking with Experts | There is sense behind this seemingly irrational behavior. Humans’ tendency to “overimitate”—to reproduce even the gratuitous elements of another’s behavior—may operate on a copy now, understand later basis. After all, there might be good reasons for such steps that the novice does not yet grasp, especially since so many human tools and practices are “cognitively opaque”: not self-explanatory on their face. | 2023-07-04 00:59:05 |

| Thinking with Experts | reenacting the experience of being a novice need not be so literal; experts can generate empathy for the beginner through acts of the imagination, changing the way they present information accordingly. An example: experts habitually engage in “chunking,” or compressing several tasks into one mental unit. This frees up space in the expert’s working memory, but it often baffles the novice, for whom each step is new and still imperfectly understood. A math teacher may speed through an explanation of long division, not remembering or recognizing that the procedures that now seem so obvious were once utterly inscrutable. Math education expert John Mighton has a suggestion: break it down into steps, then break it down again—into micro-steps, if necessary. | 2023-07-08 00:01:34 |

| Thinking with Experts | third difference between experts and novices lies in the way they categorize what they see: novices sort the entities they encounter according to their superficial features, while experts classify them according to their deep function | 2023-07-08 00:02:33 |

| Thinking with Experts | Experts have another edge over novices: they know what to attend to and what to ignore. Presented with a professionally relevant scenario, experts will immediately home in on its most salient aspects, while beginners waste their time focusing on unimportant features. | 2023-07-08 00:02:59 |

| Thinking with Experts | These strategies—breaking down agglomerated steps, exaggerating salient features, supplying categories based on function—help pry open the black box of experts’ automatized knowledge and skill. | 2023-07-08 00:03:40 |

| Thinking with Peers | Our brains evolved to think with people: to teach them, to argue with them, to exchange stories with them. Human thought is exquisitely sensitive to context, and one of the most powerful contexts of all is the presence of other people. | 2023-07-08 00:07:29 |

| Thinking with Peers | To offer just one example: the brain stores social information differently than it stores information that is non-social. Social memories are encoded in a distinct region of the brain. What’s more, we remember social information more accurately, a phenomenon that psychologists call the “social encoding advantage.” | 2023-07-08 00:08:08 |

| Thinking with Peers | social interactions with other people alter our physiological state in ways that enhance learning, generating a state of energized alertness that sharpens attention and reinforces memory. Students who are studying on their own experience no such boost in physiological arousal, and so easily become bored or distracted; they may turn on music or open up Instagram to give themselves a dose of the human emotion and social stimulation they’re missing. | 2023-07-09 00:05:45 |

| Thinking with Peers | Such outcomes may be due, in part, to the experience of what psychologists call “productive agency”: the sense that one’s own actions are affecting another person in a beneficial way. | 2023-07-09 00:07:21 |

| Thinking with Peers | It is “a general rule of teaching,” he has written, “that if an instructor does not create an intellectual conflict within the first few minutes of class, students won’t engage with the lesson.” | 2023-07-09 00:13:23 |

| Thinking with Peers | “constructive controversy,” or the open-minded exploration of diverging ideas and beliefs. In his studies, Johnson has found that students who are drawn into an intellectual dispute read more library books, review more classroom materials, and seek out more information from others in the know. Conflict creates uncertainty—who’s wrong? who’s right?—an ambiguity that we feel compelled to resolve by acquiring more facts. | 2023-07-09 00:13:40 |

| Thinking with Peers | Intellectual clashes can also generate what psychologists call “the accountability effect.” Just as students prepare more assiduously when they know they’ll be teaching the material to others, people who know they’ll be called upon to defend their views marshal stronger points, and support them with more and better evidence, than people who anticipate merely presenting their opinions in writing. | 2023-07-09 00:14:01 |